For many years now, I have worked with and been close to the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. Not only out of love for classical music, but also out of respect for this ensemble, which has proved that it does not merely rely on public funding, but also strives to “give something back” to the institutions that support it and to its audience. In a wide range of unforeseen circumstances, from the Covid-19 pandemic to the recent tragedy in Crans-Montana, the orchestra has always found a way to respond swiftly, without hysteria or excessive pathos, but with professionalism and dignity.

Fortunately, the OSR’s socially oriented work is visible not only in times of crisis. In “peacetime” as well, the orchestra collaborates with the student orchestra of the Geneva Music Conservatory, giving young musicians the opportunity to work both with leading conductors and with more experienced instrumentalists. Jonathan Nott, who led the orchestra for ten years, continued this tradition. Although before settling in Geneva his conducting career was largely associated with German opera and symphonic orchestras, and although he was known in professional circles primarily as a specialist in the German repertoire (or his first performances with the OSR in October 2014 he chose Mahler’s Seventh Symphony and Beethoven’s Fifth) over the years he has also developed a deep affinity for French and Russian music, which have formed the Orchestra’s core repertoire since its founding.

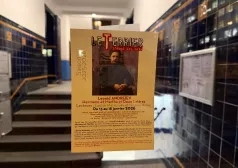

And now, having exchanged his position as Music Director/ Chief Conductor of the OSR for that of guest conductor, Maestro Nott, who will take up the post of Music Director at Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu this September, invites music lovers to a joint concert by the two orchestras. The program features two works: The Pines of Rome, the second symphonic poem from Ottorino Respighi’s so-called “Roman Trilogy,” composed in 1924, and the lyrical fantasy for orchestra, soloist, and choir L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, completed by Maurice Ravel in 1925 after six years of work. At first glance, there seems to be no “Russian accent” here. But let us take a closer look.

In The Pines of Rome, there is indeed no obvious Russian accent, unless one takes into account the philosophy-of-history idea according to which Moscow is the “Third Rome,” the spiritual and political successor to the Roman Empire and Byzantium, the last stronghold of Orthodox Christianity after the fall of the First Rome in 476 and the Second Rome, Constantinople, in 1453. (This idea, formulated by the Pskov monk Philotheus in his letters around 1523–1524 and justifying Russia’s special, messianic mission as the defender of Orthodoxy, continues to haunt certain heated minds even in contemporary Russia.)

But did you know that these Pini di Roma, “pines of Rome”, these evergreen Italian symbols, often live for up to five hundred years? That Pinocchio who entered Russian literature under the name Buratino thanks to Aleksey Tolstoy, was carved from a pine log? That a pine grove near Ravenna was immortalized by Sandro Botticelli at the end of the fifteenth century? And finally, that the poem Letters to a Roman Friend (1972) by Joseph Brodsky, who was deeply in love with Italy, ends with the following quatrain:

There, with the wind, a boat beats in a welter.

Behind a fence of pine trees, Pontus rises.

There, on the cracking bench – Pliny the Elder.

And thrushes chirp in thick locks of the cypress.

There you have your “Russian accent.” It can also be heard in Ravel’s work. The premiere of his one-act opera-ballet L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, to a libretto by Colette, took place on March 21, 1925, at the Monte Carlo Opera, conducted by the Italian conductor and composer Victor de Sabata, with the participation of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which had been spending their winters on the French Riviera since 1922. The choreography was created by the twenty-one-year-old George Balanchine, born in St. Petersburg as Georgy Melitonovich Balanchivadze, a Russian-American choreographer of Georgian origin. This was Balanchine’s first choreographic work outside Russia. In his book The Story of My Ballets, published in French in 1969 by Fayard, he wrote: “From 1925 onward, I began rehearsing the ballets in Diaghilev’s repertoire, while continuing to dance and choreograph ten new works. How could one ever forget those rehearsals, when the person standing next to me was… Ravel himself?”

The relationship between Diaghilev and Ravel, however, was not an easy one. The composer described Sergei Pavlovich as “the most charming and the most treacherous impresario.” They were staying at the same hotel in Monte Carlo, the Hôtel de Paris, where an unfortunate incident occurred. Ravel refused to shake Diaghilev’s hand, and eight days before the premiere Diaghilev threatened to withdraw all the dancers of his company from the production. But the administrator of the Société des Bains de Mer, René Léon, managed to reconcile them, the matter was resolved, and the premiere went ahead.

The press office of the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande shared another interesting story. It turns out, that Ravel had initially been skeptical about the orchestra’s founder Ernest Ansermet’s proposal to perform L’Enfant et les Sortilèges in concert form, without staging. But the conductor proved to be right, for the music is so powerful and enchanting that every listener can give free rein to their imagination and return to the world of childhood fears and dreams.

As I discovered, among the musicians of the student orchestra there are two violinists, the Russian Maria Kalugina and the Ukrainian Irina Borisova, and the vocal part will be performed by the Russian Savely Andreev. Unfortunately, Irina declined to speak with me, albeit in the most polite manner. Savely was indisposed, but Maria and I had a very nice conversation. A native of St. Petersburg, she began her musical studies at the Mussorgsky College in her hometown and continued at the Central Music School in Moscow. In 2019, she came to Geneva to fulfill her dream of studying under Alexander Rozhdestvensky. Today, Maria is completing a second master’s degree in pedagogy and plans to teach. She has not yet performed the works on the upcoming concert program, but she worked with Jonathan Nott five years ago and found the experience deeply inspiring. “I have many friends among the students and musicians of our multinational orchestra, whose lineup changes regularly, and I have never encountered either conflicts or negative attitudes toward myself,” Maria told me at the end of our conversation, which made me very happy. Isn’t it wonderful that, despite everything that divides them today, young people can still communicate in the universal language of music, without paying attention to accents?

Come, dear friends, to the concert to support them!

You can find practical information and book tickets here.