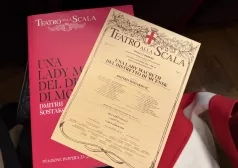

“This year, the season will open with Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, a controversial, sensual, and revolutionary work, long censored for its audacity and today acknowledged as a masterpiece of twentieth-century music.” This is how the Italian broadcaster RAI put it on 7 December, transmitting live from Milan the premiere of the production that brought the musical year to a close, the year marked by the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Dmitri Dmitrievich Shostakovich.

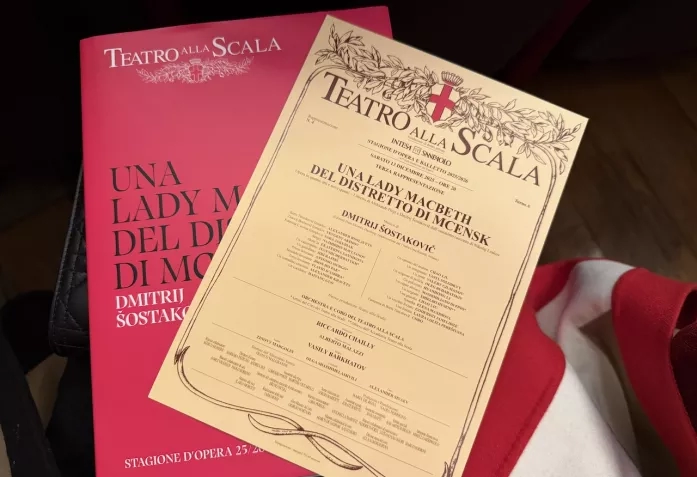

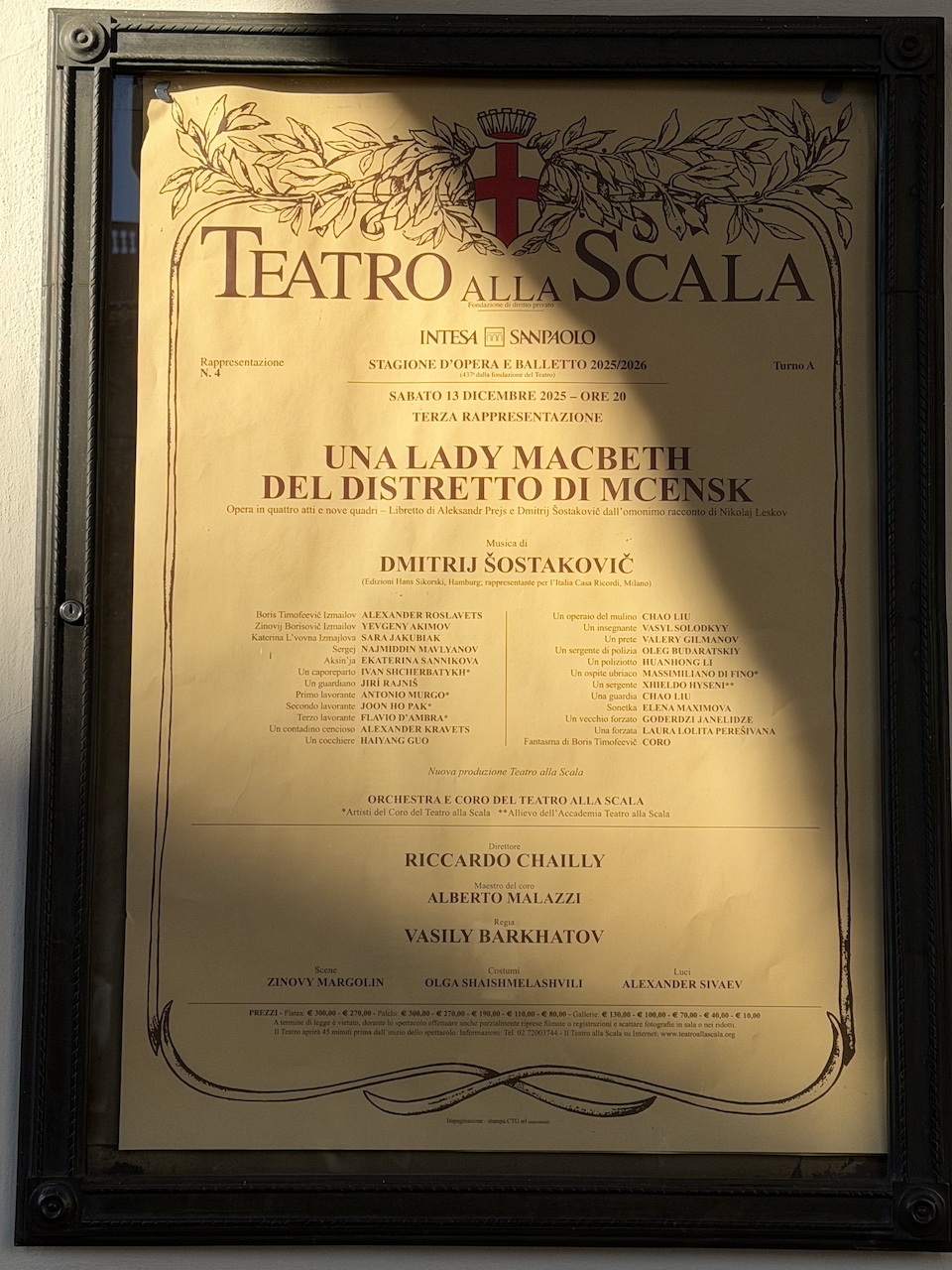

As it happened, over the past two and a half years this was already my third Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. The first, staged by the Spaniard Calixto Bieito, I saw at the Grand Théâtre de Genève in May 2023. My review was entitled “Russian Filth and Russian Sex on the Geneva Stage,” which summed up that production quite well, in my humble opinion. The second review, devoted to the production by the Catalan director Àlex Ollé at Barcelona’s Liceu, bore the title “Corpses on the Rambla.” This title reflected the director’s reading, which emphasized the criminal dimensions of Nikolai Leskov’s novella while adopting the interpretation of the main character proposed not by the writer but by the composer. For Shostakovich, Katerina is not merely a domineering woman who quite literally walks over corpses to achieve her goal; she is also a victim. At the time, I regretted not having heard the American soprano Sara Jakubiak in the role of Katerina Izmailova, and I was delighted to learn that she was invited to La Scala this time. Above all, however, I wanted to discover the interpretation of the opera proposed by the Russian director Vasily Barkhatov, whose work I had not yet seen. For this graduate of Moscow’s GITIS Theatre School, a prizewinner in Russia and the author of numerous productions across Europe, including a recent Boris Godunov at the Opéra de Lyon, this was his first encounter with Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, just as it was for Riccardo Chailly, the Italian conductor born in Milan and a great devotee of twentieth-century music. His enthusiasm clearly carried over to La Scala’s orchestra, which proved impeccable in confronting Shostakovich’s formidable and demanding score at the premiere—the ovation for all the participants lasted eleven minutes!

After watching the live broadcast, I attended the third performance, which professionals generally consider the most revealing: by that point, everyone is fully warmed up, the performers have found their bearings, and, moreover, the experience in the auditorium produces quite different emotions. All the more so since real life turned out to be no less dramatic than what unfolded on stage. Indeed, during the second performance, on December 10th, Riccardo Chailly suffered a sudden malaise. He nevertheless insisted on continuing to conduct until the second intermission, after which an ambulance had to be called for his emergency evacuation. The third act was cancelled.

… And so, on my way to Milan, while admiring the scenery passing by outside the train window, I was wondering who would conduct the orchestra of the Teatro alla Scala on December 13th. (Let me hasten to say that the pre-Christmas miracle did occur: the maestro returned to his post and was greeted with an ovation even more frenzied than usual!) I also found myself reflecting on a question posed shortly before by a friend: what is the difference between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth? The question initially struck me as odd, yet it kept returning to my mind and deserved an answer. So, apart from the gender of the protagonists, where does the real difference lie?

Macbeth is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, first published in 1623, which inspired Giuseppe Verdi’s opera of the same name in 1846–1847. Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District is a novella by Nikolai Leskov, completed in Kyiv on 26 November 1864, which inspired Shostakovich’s opera in 1932. After its premiere in January 1934 at the Maly Opera in Leningrad—MALYGOT in the Russian abbreviation—under the baton of Samuil Samosud, and in Moscow a year later, the work provoked the condemnation of the composer by the leadership of the Communist Party of the USSR and was banned. It was not until 1962 that it was staged in Moscow in Shostakovich’s self-censored version under the title Katerina Izmailova, and only in 1978 that it was restored to its original version, in London.

Shakespeare’s hero is the military leader Macbeth, driven to crime by a thirst for power, the witches’ prophecies, and the influence of his wife. His Lady Macbeth is a conscious accomplice, a cold strategist, the embodiment of destructive ambition, described as a “fiend-like queen” at the end of the play. In Leskov, by contrast, the heroine Katerina Izmailova commits a series of murders out of passion and loneliness. What a terrible thing loneliness is, what a dangerous counsellor.

The scope of these two tragedies differs profoundly as well. Macbeth is a philosophical tragedy of power, crime, fate, and expiation. Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District is a socio-psychological tragedy about the condition of women, violence, stifled freedom, and destructive passion. The former is a tragedy of the state; the latter, that of a private, everyday life in the mercantile world of the Russian provinces. Provinciality is emphasized in the title itself, which lends Leskov’s Lady Macbeth an ironic dimension. His heroine is not a court intriguer but a passionate woman, whose crimes are born of distress and despair and lead her to ruin, both moral and physical. Tragedy of power vs. tragedy of passion.

Katerina Izmailova has every reason to fall into despair: beautiful, young, and ardent, she lives with an old and weak husband, incapable even of giving her a child. She therefore throws herself into the arms of the young clerk Sergei, and events follow inexorably. What woman could fail to understand her? Sara Jakubiak understands her deeply: “Is Katerina a bloodthirsty murderess or a feminist? I think Shostakovich wanted her to be a bit of both. Personally, I feel great empathy for her. I understand what she does and why she does it. I, Sara, would act differently, and many others would as well, but there is something profoundly human in her that anyone can identify with, even though she is a murderer. For me, Katerina Izmailova is a woman inhabited by an inner dictator. In the opera, we see various dictators around her who control her, but the true dictator is within her—it is passion. She acts under its sway, kills for it, loves through it, and it is through it that she finds her freedom.” From now on, it is impossible for me to imagine Katerina, that beauty in the style of a Russian painter Boris Kustodiev, other than crowned with the flaming red hair of the American singer. A lioness in a cage.

There will always be those who find no excuse for Katerina, and that is precisely what makes this character so compelling—the only truly ambiguous figure in a gallery of almost caricatural portraits. She is a living being, loving and suffering. But do the torments she endures signify genuine remorse? I am not sure. One cannot, however, doubt that this strong-willed woman loves sincerely: “Sergei, I have not seen you all day,” she sings already at the penal colony, recalling Lensky in Eugene Onegin with his “Long is the day spent away from you, it is an eternity!”, addressed to Olga.

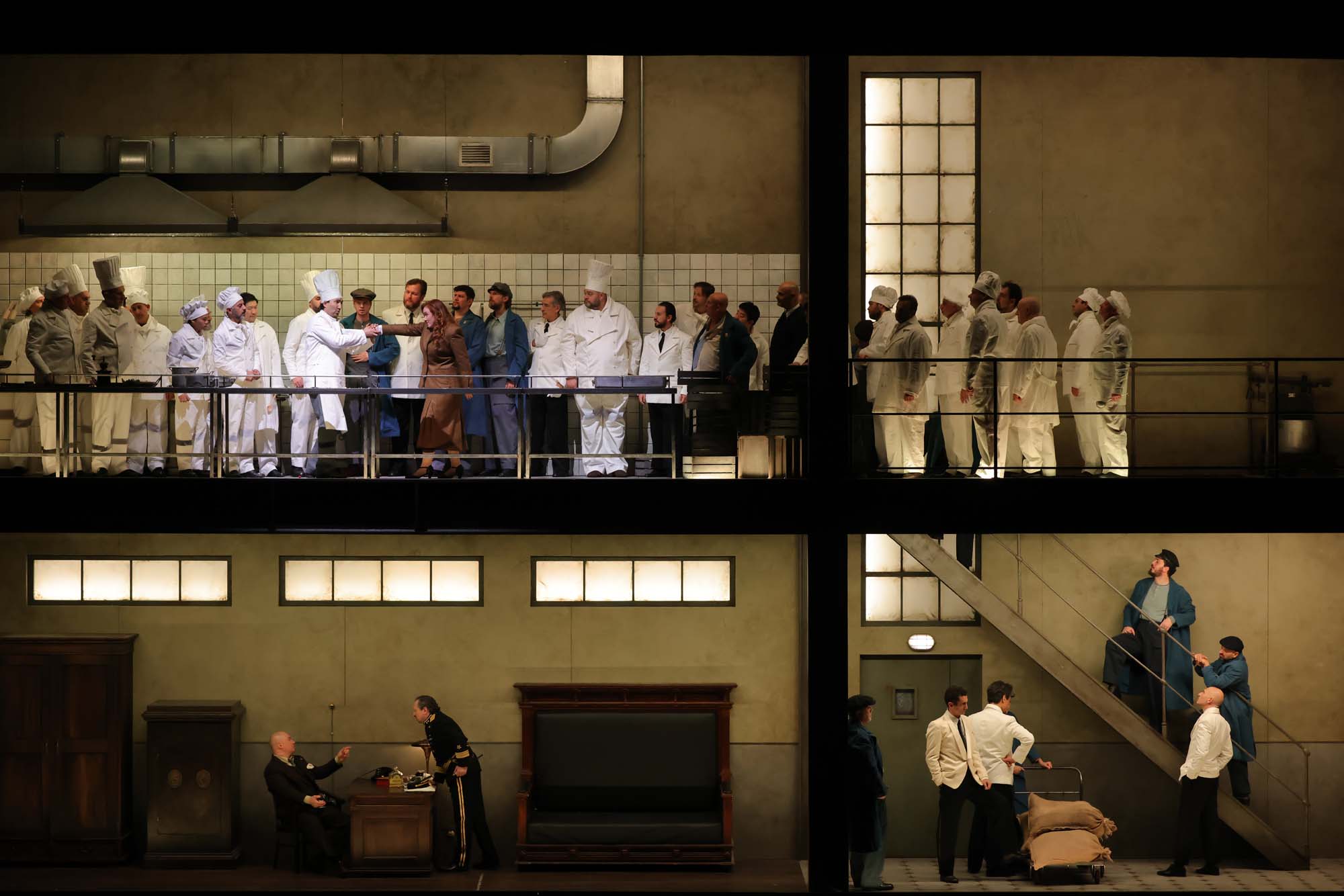

Vasily Barkhatov transposed the action from the second half of the nineteenth century to the grim 1930s, the period when the opera was composed. The transposition is carried out with great delicacy, without heavy-handed external signs. The first curtain reveals portraits of Katerina Izmailova, front and profile, as well as the cover of her “case file.” The criminal is questioned at the front of the stage by a gendarme. She is still wearing her wedding dress—she was arrested at her own wedding. The second curtain reveals a dining room whose interior is far too luxurious for a provincial town. Here you have the Empire style, Stalinist version, with its unique eclectic pomp: soaring ceilings that allow the action to unfold simultaneously on two levels, monumental chandeliers, leather sofas, administrative desks, and even a coffin upholstered in red. Bravo to the set designer Zinovy Margolin, a graduate of the Belarusian Institute of Theatre Arts.

From the very first scene, the power relations are established. “Why were you even taken into this house?”, “You are as cold as a fish, you do not even try to win caresses,” Boris Timofeyevich Izmailov hurls at his daughter-in-law, a wealthy merchant and domestic despot inclined to paranoia. “I do nothing but keep watch for burglars,” he will sing in the second act. (The bass Alexander Roslavets, born in Brest, Belarus, and a graduate of the Saint Petersburg State Conservatory, who had already won me over in this role in Geneva two years ago and in January 2025 in Lucerne, only confirmed that impression here.)

As for the man whose caresses Katerina is supposed to win, he is hardly inclined to provide it: her husband, Zinovy Borisovich, is too old, too corpulent, and above all a coward that is frankly repellent. Before leaving the house, he asks his father to keep an eye on his wife and ensure that she obeys him. (The tenor Evgeny Akimov, also a graduate of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, performs this ungratifying role brilliantly.) Izmailov senior, for his part, snickers and displays a certain worldliness as he lectures on young wives, who supposedly need nothing more than “s’il vous plaît” and “rendezvous.” French is, for him, quite evidently the language of debauchery.

Meanwhile, the screen displays the case file on Sergei, the new clerk, who “has everything going for him—height, face, beauty.” And who can read, unlike Katerina herself. And who knows how to understand and sympathize: “I have seen enough of women’s condition.” How can one resist? All the more so as La Scala’s casting is remarkable: the tenor Najmiddin Mavlyanov, born in Samarkand, whom I had noticed in Geneva’s production of Fedora last year, corresponds perfectly to this description. And he sings, to boot.

The scene of the attempted gang rape of the cook Aksinya, very convincingly performed by Ekaterina Sannikova, also a graduate of the Saint-Petersburg Conservatory though born in Ternopil, is, like all the numerous sexual scenes in this opera, a true ordeal for the director—a test to his taste. In my view, Vasily Barkhatov chose the only right approach, judging that Shostakovich’s music, literally oozing sensuality, has no need of additional visual effects. He thus spared the audience the vulgarity that has lately become almost the norm.

There are two moments in this production that, in my view, betray Vasily Barkhatov’s “Russian accent” and require explanation for a foreign audience.

The first occurs at the beginning of the second act, when Boris Izmailov is carousing with a gendarme (Jiří Rainiš), a priest (Valeri Gilmanov), and a “Shabby lout.” Ah, how difficult it is to translate precisely the Russian term Zadripanny muzhichonok: the “shabby lout” is deliciously repellent in the interpretation of the Ukrainian tenor Alexander Kravets, with whom I conducted an interview as long ago as 2007. Izmailov is the leader of the group, and suddenly he produces a hockey stick. At first glance, nothing special—unless one knows that hockey is one of the Russian president’s favourite sports, unless one understands the very nature of the circle surrounding Izmailov (the Church, the forces of law and order, and a tamed representative of “civil society”), and unless one is familiar with the popular Soviet song proclaiming that “real men play hockey; cowards do not.” The “real men” are represented in all their “splendour” in this production, it must be said.

The second moment concerns a small volume of Gogol held by the priest in place of a Bible. The cover of the book is blue, so it is most probably from the 1952 edition of Gogol’s Complete Works. In other words, Stalin is still alive. It is unlikely that spectators, even those in the front rows, will immediately notice this small volume, which one of the characters will brandish a little later. Yet it is precisely this allusion to Gogol that illuminates the caricatural nature of many of the characters and explains why Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was described by Shostakovich himself as a satirical tragedy. This is what we, back home, call Russian black humour.

Everything else needs no explanation. The director’s remarkable “trick” lies in the scenes of depositions. Throughout the performance, the characters testify against one another—in other words, they denounce. This “trick” does not merely fill scenic pauses; it conveys the “noise of time,” to use the expression of the poet Osip Mandelstam, that time in which we are all “prisoners,” as in Alexander Stein’s play, miraculously staged in 1970, at the height of the period of stagnation, at Moscow’s Theatre of Satire, and which posed an essential question to the audience: must the artist serve his time, or does he have the right—or even the duty—to resist it? All this, I am sure, is perfectly clear to the contemporary spectator. It is equally clear that the authorities’ reaction to denunciations is selective, dictated by mood. The Izmailovs did not invite the chief of gendarmes to their wedding; they “turned up their noses”—and this is their punishment. Personal revenge, envy, and inferiority complexes are the true driving forces behind many tragedies, whatever lofty “ideals” they may claim to serve.

The choruses in Shostakovich’s opera are likewise perfectly legible to today’s audience. Inherited from the great Greek tragedies—the mother figures, so to speak, of all later tragedies—they usually embody the voice of the people, vox populi. One need only recall the famous Chorus of the Hebrews in Verdi’s Nabucco or the choruses in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. But one should note the contrast between the chorus of venal and corrupt gendarmes (“Where and how to line one’s pockets”), and that of the convicts being led to the penal colony in the final of the third act (“Ah, those infinite spaces, / those endless days and nights, / our thoughts without solace, / and those heartless gendarmes…”). One then has the impression that there are two peoples in Russia, and that the abyss between them is immense.

And finally. Vasily Barkhatov has allowed himself to modify the ending: Katerina and Sonyetka, who at the penal colony has taken both the woollen stockings and Sergei from the “the rich merchant”, do not drown in the lake, as they should according to the libretto. But let us not rush to accuse the director of sacrilege! True, Katerina sings her final aria not while gazing at the forest lake, where “the water is black like my conscience,” but at a jerry can of petrol. Heaven knows how she managed to obtain it. Her final instrument of murder, after the poisoned mushrooms (for her father-in-law) and the pillow (for her husband), is a simple box of matches. One gesture, and she and Sonyetka are transformed into two pillars of fire.

Who were historically burned at the stake? Witches. And how does Macbeth begin? With the scene of the witches and their formula: “Fair is foul, and foul is fair.” By this single stroke, Vasily Barkhatov endows the Russian provincial drama with the power of a Shakespearean mythical tragedy.

Bravo.