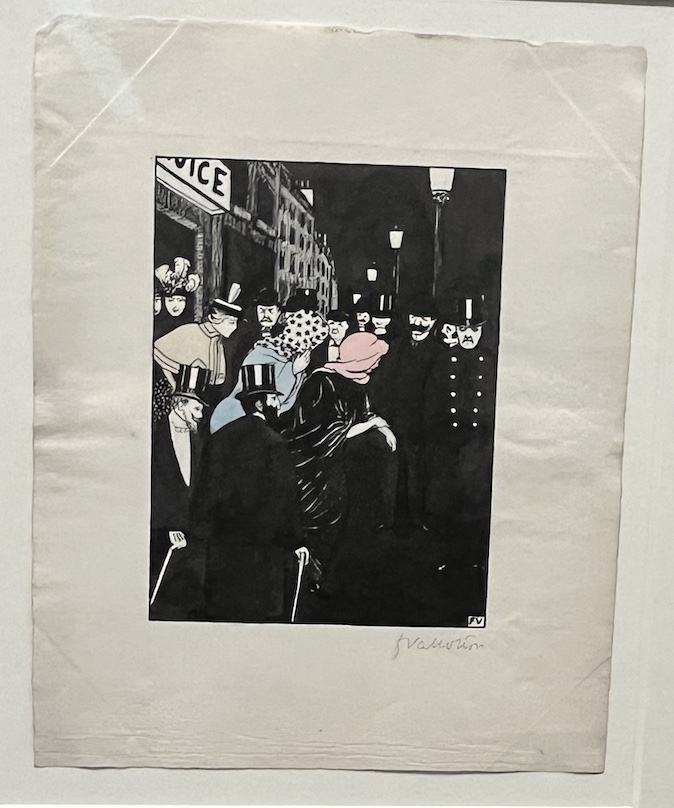

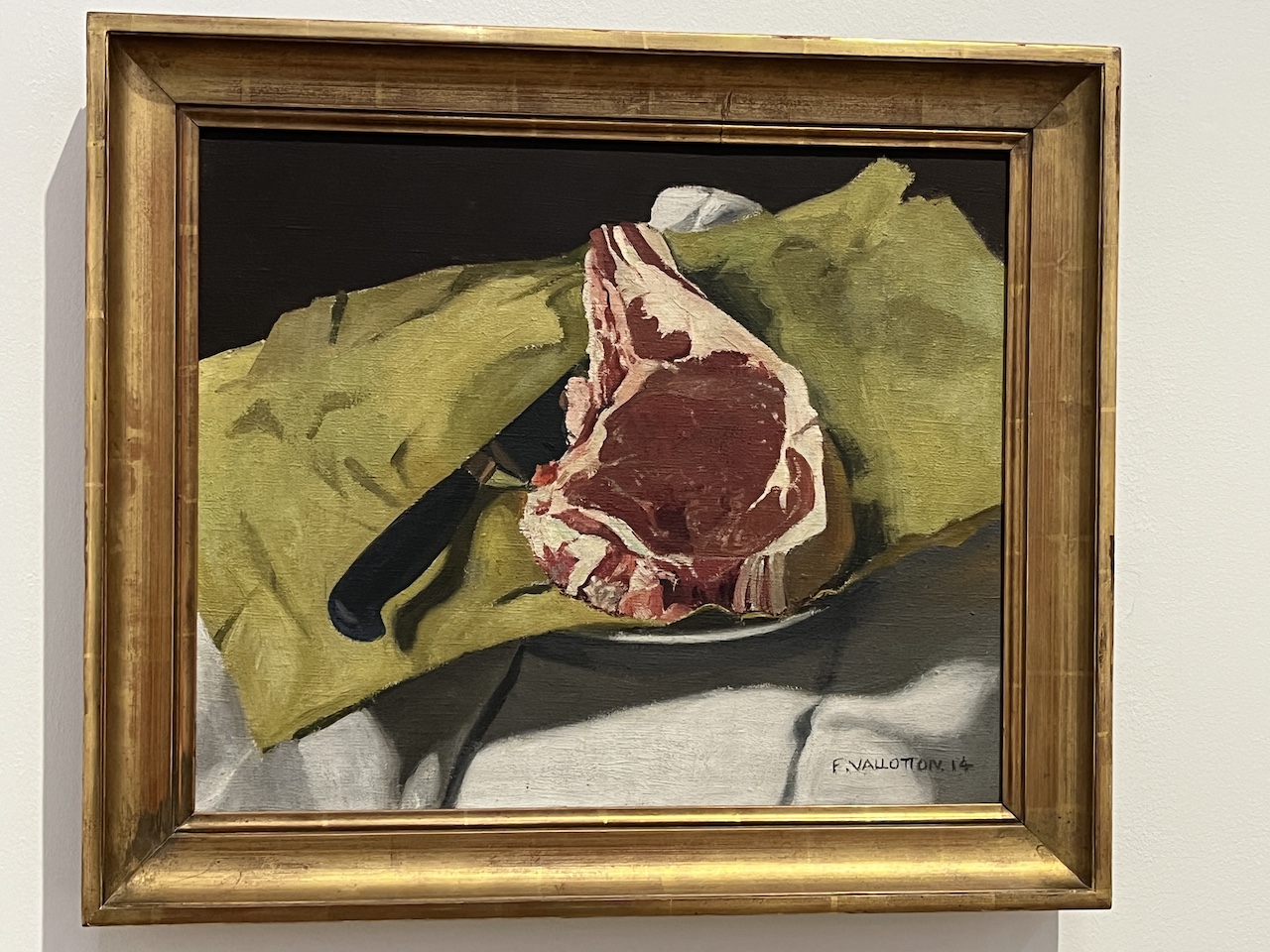

In the pages of Nasha Gazeta devoted to Swiss politics or daily life in the country, the “Röstigraben” often comes up – that linguistic and cultural divide separating the French- and German-speaking regions. The topic usually invites humour, though at times it touches on serious matters. Yet there are also signs that the two major linguistic parts of Switzerland can come closer together. A few weeks ago, for example, the evening newscasters of RTS and SRF “switched languages”: in Zurich, the 7:30 p.m. news was presented in French, and in Lausanne, in German. And while major works by Félix Vallotton from the Kunsthaus collection are on view at the MCBA in an exhibition entitled Vallotton Forever, the country’s largest art museum has chosen to introduce its multinational public to the work of an artist “from the other lake”.

In two rooms of the museum’s historic Moser wing, near the exhibition Masterpieces on Paper from Albrecht Dürer to Dieter Roth, twenty-two works by Alice Bailly are displayed. They include oil paintings, drawings and, above all, her celebrated tableaux-laine, wool paintings, now regarded as a milestone of Swiss modernism.

NashaGazeta.ch had already mentioned this artist when presenting the Hahnloser family collection in Bern, where a portrait by Bailly hung beside works by Matisse and Hodler. Yet I had never recounted her life in detail. It is time to do so.

Alice Bailly was born in 1872 in Geneva to a modest family. Her father, a postal employee, died when she was fourteen. Her mother, a teacher of German, instilled in her daughters a love of culture. In Geneva, Alice attended the École des demoiselles, attached to the École des Beaux-Arts, which remained closed to women at the time. She also spent time in the Valais, where she created a series of engravings known as Les scènes valaisannes. But who could resist the call of France?

In 1906, she moved to Paris, joining the “Swiss colony”, and met Cuno Amiet, Sonia Delaunay, Raoul Dufy and Marie Laurencin. Her enthusiasm carried her from Fauvism to Futurism, Cubism and Dadaism. Her talent was such that she received the federal arts grant three times in a row! In 1907 she discovered Brittany, where the landscapes and light inspired her Scènes bretonnes, a format that seemed to resonate deeply with her. For several years she divided her life between Paris and Geneva. She returned to her native city at the outbreak of the First World War, then settled permanently in Lausanne in 1923. She remained there until her death on 1 January 1938, in her studio. Her passing has been attributed to the exhaustion caused by eight monumental mural panels commissioned in 1936 by the Lausanne Municipal Theatre – today’s Théâtre de Vidy – a labour thought to have precipitated the development of tuberculosis. In her will, Bailly established a fund to support young Swiss artists, sustained by the proceeds from the sale of her own works.

And these works did indeed sell well. She first exhibited in 1900, later taking part in the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne in Paris, holding a solo exhibition at the Musée Rath in Geneva in 1913, and showing her work in Munich, Bern, Neuchâtel, the Kunsthaus Zürich and even Athens. According to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, where some of her works are also preserved, she was selected in 1912 to represent Switzerland in a travelling exhibition that visited Russia, England and Spain. In 1926 she received an award at the Venice Biennale.

“Bailly was not only a pioneer through her work; she was also considered one of the most modern artists of her time, rejecting gender boundaries and defying traditional role stereotypes,” recalls the Kunsthaus Zürich press release. The exhibition curators, Philippe Büttner and Maja Wismer, draw special attention to her tableaux-laine, now recognized as innovative, though in her lifetime they were dismissed as mere craft experiments.

While acknowledging the originality of these wool compositions – Pink Spring (1917) is truly exquisite – I found myself even more moved by other works: Archers (1911), clearly inspired by Hodler, the Geneva Waterfront or Gull Flight of 1915, and the portrait of the artist’s sister, Louise, painted in 1913.

As I continued through the exhibition, I stumbled upon an unexpected “Russian trace”. The caption for Woman at the Mirror or Woman at her Toilette, painted in 1918, notes that the model is Lioudmila Botkina. Who was she? The museum could not provide details, and the only person bearing this name who matches the profile, according to my research, is the daughter of the renowned physician Sergei Botkin, whose name the Moscow hospital still bears. Born in 1886 from his second marriage to Princess Ekaterina Obolenskaia, Lioudmila was working as a nurse in a hospital for wounded soldiers of the Russian Expeditionary Corps in Montpellier in 1917, when she met her future husband, Piotr Chekhov, a relative of the great writer. After obtaining his medical degree, he served as a military doctor in the French army during the First World War. An unexpected parallel story as intriguing as it is touching.

The exhibition runs until 15 February 2026, and I warmly recommend it. All practical information is available on the Kunsthaus Zürich website.