For many years, I supported the Geneva film festival Black Movie, which exists in part thanks to my Swiss taxpayer’s money. I supported it because its programmes always included films made in the post-Soviet space that interested me. But a year ago, I swore that I would no longer do so, after the French LFI member of the European Parliament Rima Hassan, who publicly supports Hamas, was invited as a speaker and guest of honour. Fortunately, legal proceedings have since been initiated against her for condoning terrorism, and she will have to answer for her actions before the French court. I can therefore break the vow I made to myself and speak to you about Sergei Loznitsa’s film Two Prosecutors, which matters to me infinitely more than this highly controversial figure.

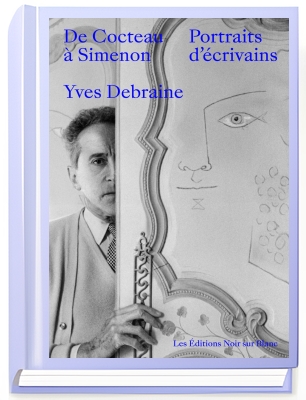

I first met Sergei Loznitsa in 2019. It feels as though it happened in another life. That year, Black Movie screened his film Victory Day, and the interview we recorded was entitled “One Must Tell the Whole Truth, All the Way”. Since then, I have followed his work closely and have been pleased to present to my readers his documentaries State Funeral and Babi Yar. Context, both of which have received numerous awards.

On 28 February 2022, as one can read on the director’s Wikipedia page, Sergei Loznitsa left the European Film Academy, judging its reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to be insufficient. “For four days now, the Russian army has been devastating Ukrainian towns and villages, killing Ukrainian civilians. Are you, humanists, defenders of human rights and dignity, supporters of freedom and democracy, afraid to call the war by its name, to condemn barbarism and to express your protest?” The following day, the Academy issued a stronger statement calling for a boycott of Russian cinema. In response, Loznitsa condemned this boycott: “Many friends and colleagues, Russian filmmakers, have spoken out against this senseless war. They are human beings. Like us, they are victims of this aggression.” On 18 March 2022, the Ukrainian Film Academy expelled him for opposing the boycott. On 21 May of the same year, upon receiving an award in Cannes for his contribution to the art of cinema, the director delivered a speech against calls to boycott Russian culture, stressing that demanding the banning of a culture amounts to demanding the banning of a language, an approach that is “archaic and destructive by nature”, “as immoral as it is absurd”.

It takes extreme courage to dare to say such things, courage bordering on madness. But all of us who grew up in the USSR were raised in the cult of the “madness of the brave”, repeating the words by Maxim Gorky in The Song of the Falcon that have become classics: “The madness of the brave, that is the wisdom of life!” Sergei Loznitsa did not limit himself to declarations. The leading roles in his film Two Prosecutors, shot in Russian, are played by well-known Russian actors opposed to the war, who have left Russia for various destinations but have nonetheless not ceased to be Russian. How did he dare? And why return to the theme of Stalinist repressions, which some consider exhausted, even tedious, having been treated so often, frequently by attempting to place crime and grandeur on the same scale to see which would prevail, while in real-life Russia monuments to Stalin continue to multiply?

The film Two Prosecutors was made thanks to the collaboration of French, Dutch, German, Latvian, Lithuanian and Romanian production companies. The credits, however, give particular prominence to Saïd Ben Saïd, a French producer born in Tunisia. Why? The film was selected for the official competition at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival and received the François Chalais Prize, an award given each year to films that embody the values of journalism and highlight the presence of journalists at the festival. That year, I did not go to Cannes, but I was absolutely determined to see the film. I thank Sergei Loznitsa for the trust he placed in me by sending me a link, in exchange for my promise not to write anything before the film’s release in Switzerland. The time has come.

You know the importance I attach to literary works that serve as the basis for creations in other genres, be it opera, theatre or cinema. I will therefore begin, once again, with that. Sergei Loznitsa wrote the screenplay for his film himself, based on the eponymous novella by Georgy Demidov. This author is little known. I confess that I myself had never heard of him. And yet, he is worthy of becoming the hero of a novel yet to be written and already served as the prototype for the characters in the works of Varlam Shalamov, author among others of Kolyma Tales. Georgy Demidov’s life is tragically representative of his generation. A gifted physicist and a student of Nobel laureate Lev Landau, he was arrested for the first time in 1938 and sentenced to eight years in a labour camp under Article 58-10 – for counter-revolutionary activity. Arrested again in 1946, he received an additional seven-year sentence, followed by five years of deprivation of civil rights, this time for anti-Soviet propaganda. In 1958, he was rehabilitated in both cases following a renewed appeal to the Main Military Prosecutor’s Office. It was then that he began to write. And he can be trusted.

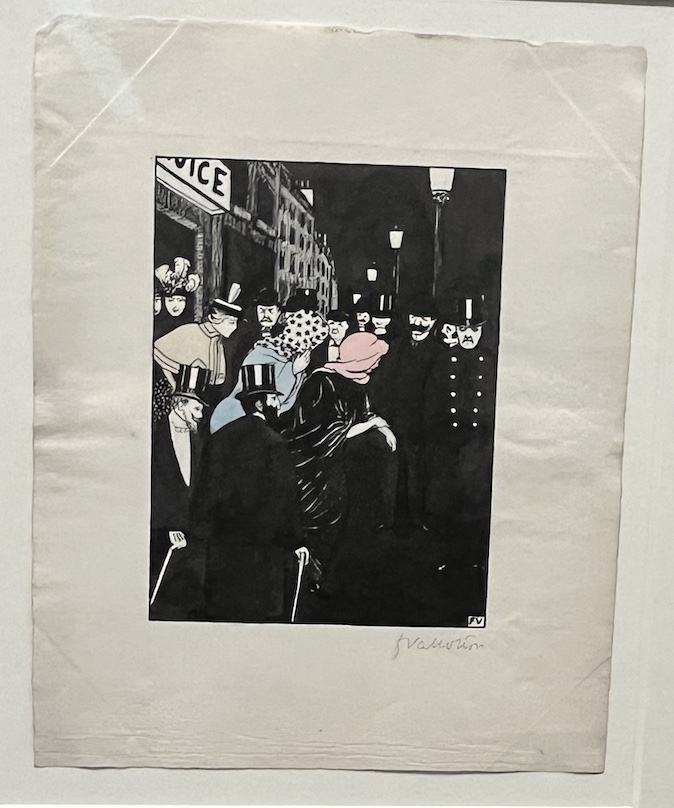

… The film begins with the opening of a padlock on the gates leading into the courtyard of the Bryansk prison, some three hundred and fifty kilometres from Moscow. “1937, the height of Stalinist terror”, read the intertitles, as a group of prisoners crosses the screen. Exhausted men, staggering, holding up their trousers with their hands for lack of belts. It was for a reason that Demidov called Kolyma, that symbol of the Gulag, “Auschwitz without furnaces”. The furnace plays a particular role in the film. One of the inmates is tasked with burning an entire sack of letters written by his fellow prisoners, victims of false accusations. They all look alike, these triangularly folded sheets addressed to Stalin, each containing an individual tragedy and a hope for justice. I anticipate a question some of you might ask: did Stalin really know nothing, if the letters never reached him? He knew. At the risk of his life, an elderly inmate does not throw one of these letters into the fire, a letter that stands out from the pile lying on the floor. It is written on a scrap of paper. Written with blood. And addressed not to Stalin but to the Bryansk regional prosecutor’s office. Its author is an old communist, Ivan Stepanovich Stepniak, detained in the section for particularly dangerous criminals.

(For this role, Sergei Loznitsa cast one of Russia’s most popular actors, Alexander Filippenko, who has appeared in more than a hundred films. By his initial training, like Georgy Demidov, he is a physicist and a graduate of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. In November 2022, at the age of seventy-seven, Alexander Filippenko left the Mossovet Theatre in Moscow and moved to Lithuania.)

… Miraculously, Stepniak’s letter reaches its addressee, Alexander Kornev, a young supervisory prosecutor who has just completed his law studies. For those unfamiliar with the term, a supervisory prosecutor holds a special function within the prosecution service: overseeing compliance with the law by state bodies, as well as the observance of citizens’ rights and freedoms, with the aim of identifying, eliminating and preventing violations, thus ensuring legality in all spheres of public life, up to and including criminal proceedings.

(In this role appears Alexander Kuznetsov, a thirty-three-year-old native of Sevastopol, a graduate of Moscow’s GITIS theatre institute, who made a brilliant start to his career. In February 2022, he signed an open letter against Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine, and in September of the same year moved to the United Kingdom.) How elegant he is in his macintosh and hat, how firm in his exchanges with the camp’s duty officer, played by Latvian actor Andris Keišs, and then with his superior, portrayed by Lithuanian actor Vytautas Kaniušonis. What nonchalance this superior displays, seated in his office beneath a portrait of Felix Dzerzhinsky, founder and head of the Cheka, the Bolshevik state’s political police, and the poster “Be vigilant!”. What calculated slowness, what persuasive force in his unequivocal warnings to Kornev about a “virus” he risks catching by insisting on meeting Stepniak. “Do you know where your predecessor is now?”, he asks. But the threats have no effect. Kornev is young and principled. He is a romantic. Romantics do not live long.

The scene of his meeting with Stepniak is central to the film. “Not stupid, honest and not a coward”, this is how the old Bolshevik characterizes the young jurist. In Stepniak’s speech, which in my view is a little too smooth in this context, is concentrated all the ambiguity of the convictions of the majority of Soviet citizens, both of his generation and of those that followed. Barely alive after torture intended to extract false confessions from him, having experienced in his own flesh the boundless power “hidden fascists of the NKVD”, believing neither the camp administration nor its guards (where on earth did Sergei Loznitsa find these… faces?), he nevertheless continues to believe in the justice of the communist system. “I am not asking for myself, my soul only aches for our revolutionary cause”, he explains to Kornev. In other words, it is not the system that is to blame, but individual executors. What can one say? How can one explain this naivety bordering on blindness, one that draws the old prisoner and the novice prosecutor so close together?

… Determined, Kornev travels to Moscow, to see the Prosecutor General of the USSR, Andrei Vyshinsky, the very man who served as state prosecutor in all three major Moscow Trials of 1936 to 1938, calling to “shoot like rabid dogs” the “traitors and spies who sold our Motherland to the enemy”, and who died of a heart attack in New York in 1954 while representing the USSR at the United Nations. Anatoly Bely is absolutely brilliant in this episodic role. (Born in Ukraine, Anatoly Bely first graduated from the Kuibyshev Aviation Institute and then from the Mikhail Shchepkin Higher Theatre School in Moscow. He spoke out against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, left the Moscow Art Theatre named after A. P. Chekhov in July 2022 and moved to Israel, where he now works at the Russian-language Gesher Theatre in Tel Aviv. On 15 December 2023, he was added by the Russian Ministry of Justice to the register of “foreign agents”.) Physically, Anatoly Bely is unrecognizable in the film, the spitting image of Vyshinsky, whom the president of the People’s Court of Nazi Germany, Roland Freisler, incidentally considered a role model.

Kornev travels to Moscow on a crowded train, where he encounters a peasant mutilated during the First World War. During the 1916 campaign, near Kovel, he lost an arm and a leg and then also made his way to the Kremlin in search of justice. In the role of this “pilgrim to Lenin”, Alexander Filippenko appears once again, reproducing with astonishing precision the characteristic manner of speech of the leader of the world proletariat. What does this directorial choice mean, given that it is clearly not a matter of a shortage of actors? And is not the speech of this character, dressed in the manner of a Russian national hero Ivan Susanin, also excessively smooth and flawless?

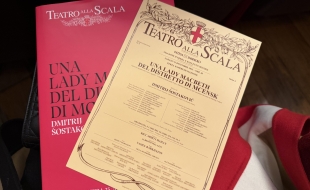

The scene in the office of Vyshinsky, “one of the busiest men in the state”, whom Kornev nonetheless manages to meet after an entire day of waiting in the antechamber, is the scene of a clash between two very different prosecutors, two systems, two visions of justice. Who do think will prevail, against the backdrop of a rousing song composed by Dmitri Shostakovich to lyrics by the poet Boris Kornilov for the film Contre-plan (original Russian title: Vstrechny), released in 1932, a song that was immediately taken up by millions of people? And not only in the USSR. In the book D. Shostakovich on Time and on Himself, 1926–1975, the composer is quoted as saying of this song: “It has long since taken flight. Across the ocean it became the anthem of progressive people, and in Switzerland, for example, a wedding song.” Residents of Switzerland, were you aware of this? Shostakovich’s fate is well known, that of Kornilov far less so. Arrested in Leningrad on false charges on 27 November 1937, he was executed on 20 February 1938 as a member of an anti-Soviet Trotskyist organisation. He was thirty years old. He was posthumously rehabilitated on 5 January 1957 “for lack of corpus delicti”.

… I will not continue to recount the film, nor will I spoil the ending for you. I sincerely hope that you will see it for yourselves. I will only say that Sergei Loznitsa succeeded perfectly in recreating the suffocating atmosphere of the Stalinist regime, with its agonising anticipation of the passing of judgement over human destinies. As for the questions that arose in my mind during the screening, I intend to ask him personally, we are due to meet soon. In the meantime, do watch an excerpt from the film Contre-plan, with that joyful, optimistic song. But why does it make one want to cry?

P.S. The filmmaker will be present to introduce this striking film and will take part in a special encounter with the audience on January 21. You will have three opportunities to see the film.