I have been following Serhiy Zhadan’s work closely since 2010, back when I would without a second thought call him “Sergey” in the Russian manner. That year he was invited to the literary festival in Loèche-les-Bains after his book Hymn of the Democratic Youth (Hymne der demokratischen Jugend) was published in German and topped the bestseller list of the German broadcaster SWR. Even earlier, in March 2008, Zhadan’s novel Anarchy in the UKR, in its Russian translation, was longlisted for Russia’s National Bestseller literary prize and received an honorary diploma at the Book of the Year competition during the Moscow International Book Fair. Yes, such things did happen. (The novel was later published in French by Éditions Noir sur Blanc, and I have written about it.)

For those who are not yet familiar with him and his work, Serhiy Zhadan was born in 1974 in the Luhansk region in eastern Ukraine. In 1996 he graduated from the Skovoroda National Pedagogical University in Kharkiv and later completed his postgraduate studies there, earning a PhD in philology. For four years he taught Ukrainian and world literature at his alma mater. He lived and worked in Kharkiv, translating poetry from German, English, Belarusian, and Russian. He was deeply involved in both literature and music, for Serhiy is not only one of the most popular writers and poets of his generation, but also a well-known rock musician and a person with a very active civic stance.

Success accompanied him. In 2014, Serhiy Zhadan received the Jan Michalski Foundation’s literary prize for his first novel, Voroshilovgrad, which had been published the previous year in French under the title La Route du Donbass by the same Lausanne-based publisher. In 2016, he was awarded the Ukrainian Book of the Year State Prize, the funds from which he donated to children’s institutions in the Luhansk region. In 2022, he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature by the Polish Academy of Sciences and received the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade for his “outstanding literary work and for the humanitarian stance with which he addresses people in wartime and helps them at the risk of his life,” as well as the Hannah Arendt Prize for Political Thought. In 2025, he was awarded the Austrian State Prize for European Literature. Literary critics unanimously note the richness of Zhadan’s language and his rare ability to combine different registers, biblical, military, political, and prison slang.

In 2022, I was pleased to present his novel The Boarding School, written in 2017 and also made available to French-speaking readers by the Lausanne publisher. At the time, I was deeply upset that Serhiy refused to speak to me in Russian. I emphasize that I was upset, but not judgmental. I liked that book very much, because in it, much as Alexander Solzhenitsyn once tried to encapsulate the entire horror of the Soviet camp system in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Serhiy Zhadan conveys the unspeakable terror of fratricidal war through three days in the life of his hero, the schoolteacher Pasha. The words spoken by the head of the boarding school in the novel have lost none of their relevance over the years: “You have spent your whole lives hiding. You have grown used to thinking that you bear no responsibility, that someone else will always sort everything out for you. No, no one will sort anything out this time. Because you saw everything and you knew everything. But you remained silent, you said nothing. Of course, no one will judge you for that, but do not expect to be kindly remembered by posterity.”

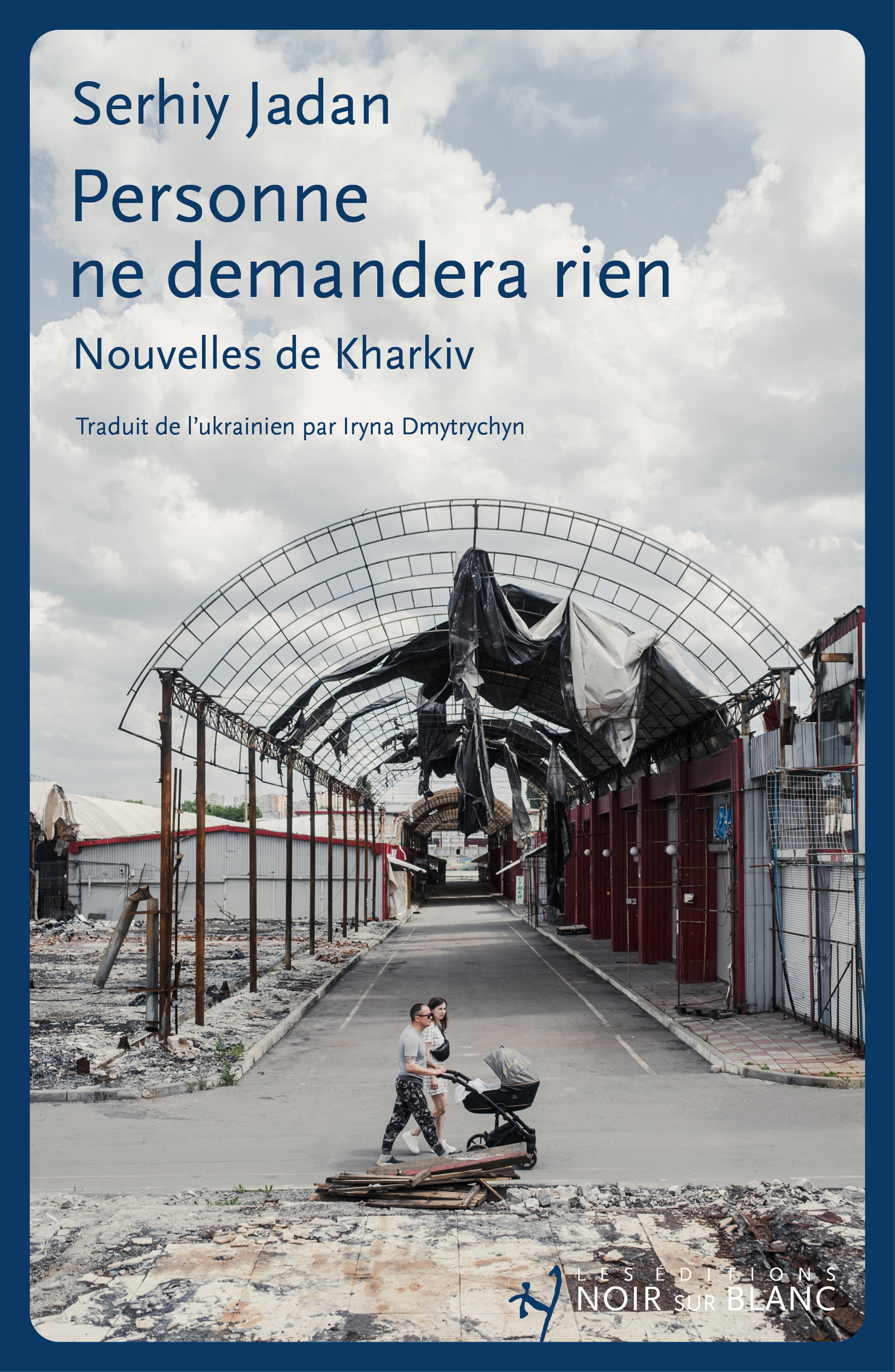

The Swiss publisher decided to title the new book No One Will Ask Anything, but its original title is Arabesques, and I would like to say a few words about it. As you know, an arabesque is a type of ornament made up of intricate interweavings of lines, scrolls, plants, and flowers, usually arranged symmetrically around a single axis. “The pattern is highly fragmented, especially dense and rich, so that the arabesque is perceived as a continuous design,” I read in a specialized dictionary. The term seems to me an ideal title for this book by Serhiy Zhadan, a collection of short stories, sometimes only one or two pages long, interwoven through the lives of their characters, each story fitting into a single overarching pattern, the pattern of war, which serves as the axis of the entire narrative. But the title also has, I think, a deeply personal subtext. The Kharkiv theatre founded by Serhiy Zhadan’s first wife and the mother of his son Ivan, Svitlana Oreshko, was called Arabesques. Svitlana passed away at the end of 2024, shortly after the book’s publication.

I read this book in French, occasionally consulting the Ukrainian original to check how certain details, carefully examining the illustrations by Serhiy Zhadan that accompany the text, and, as usual, making notes. In short, it is a book about how war maims people, each in their own way, physically and/or morally, but it maims everyone. Despite the dramatic nature of each story, the book as a whole is surprisingly light, lyrical, and poetic. The deep sadness embedded in it is, as Pushkin put it, luminous. And yet, nothing is beautified.

Serhiy Zhadan is a highly educated man and a subtle writer, and his book deserves to be read attentively and thoughtfully, with an effort to grasp the deeper meanings of what at first seem like simple words. Here is the very first sentence: “On the second of March, on the seventh day of the war, Kolya called and asked for a body to be taken away.” Is this precise indication of the “seventh day” accidental? I would venture to suggest that it is not, for according to the Bible, the seventh day of Creation is the day of God’s rest, the work of creation is complete, and man was created the day before. And now, the very next day, this man is a corpse, the corpse of a literature teacher born in 1945, who lived in a Khrushchev-era apartment, a reminder of our shared Soviet past, steeped in the smell of books, poverty, and a lack of love. “She was born during the war and died during the war. In between, she built a library.” Here you have a complete portrait of the unnamed heroine, gazing from an old photograph “from the past into the future. The future was a long life, with good and bad in equal measure. In the future there was all the unread literature. In the future there was death.”

As they are transporting the body, one of the friends, Artem, remarks on how quickly Kharkiv has emptied out. “Few people have stayed, the streets have suddenly become wide, empty, and defenseless. Like after a pogrom.” Why “pogrom”? It is known that during the Second World War, Kharkiv was captured by German troops on 24 October 1941. A military administration was established in the city in close cooperation with a municipal authority composed of local residents. At the very beginning of the occupation, thousands of people, mainly Jews, were arrested and soon shot or hanged in the city center. In early November, the municipal administration created a Judenrat. On 22 November, Jews were forced to wear yellow armbands and move into a ghetto, where, according to Soviet sources, about 15,000 people were killed, and according to German sources, 21,685. Such is the information provided on the website of the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial. Why, then, did the author use the word “pogrom” to describe another war? Was it to compare the Russians bombing Kharkiv to the Nazis, or to show that the descendants of those very “local residents” who once handed over their innocent neighbors to be slaughtered have themselves become victims, because sooner or later one must pay for not resisting evil? And then one should consider not only certain Ukrainians during the Second World War, but also certain Russians who act as if the present war does not concern them. That is how many reflections arise after just the first five pages, and every story gives rise to no fewer.

On the pages of the book, the reader encounters, sometimes repeatedly and in different circumstances, a wide variety of people united by a common tragedy. Combatants who have returned from the front blind or in wheelchairs, and those who are merely home on leave. Women who so desperately lack tenderness and love, mothers, wives, sisters, comrades-in-arms, and widows. Children with uncertain futures and old people living in the past. A priest who claims that depression is a luxury for atheists. Weddings and funerals, fleeting meetings and final farewells.

“We all pretended that we were not cold, not afraid, not lonely, and above all that we were not too troubled by the close and excessive presence of the war.” One of Serhiy Zhadan’s great merits is that he does not try to portray all Ukrainians as heroes. On the contrary, he shows their vulnerability and confusion in the face of a reality imposed upon them, a reality to which they try to adapt without making plans or promises.

At the same time, the author’s position is perfectly clear. I believe it is expressed in the following passage: “Much is forgiven to the victors. Not everything, of course, but much. Victory disarms. You look at the one who has won, and you understand what he was prepared to do for it. And what was he prepared to do? Anything. To go and tear that cursed victory out like a heart from a chest. To tear it out with hands, teeth, head, and fingernails, leaving the enemy not the slightest chance.”

Let me remind you that these words were written in 2024. In a few days, we will mark the fourth anniversary of the beginning of the war. Unless a miracle happens.

PS Books by Serhiy Zhadan are available in English, for example, this one.