My interest in the history of the Jewish community in Switzerland was sparked after I read Charles Lewinsky’s Melnitz, a gripping saga of a Swiss Jewish family from 1871 to 1945, translated into many languages, including Russian. Yet the history of Jews in Basel is far older. According to surviving documents, as early as 1223 the Bishop of Basel, Heinrich, borrowed large sums of money from the city’s Jews. At that time, Basel’s Jews, who were able to settle throughout the city rather than in a ghetto, were engaged primarily in traditional trade as well as moneylending. They held a monopoly on this latter activity, since canon law forbade it to Christians. Although these laws were not issued by Jews, it was precisely against them that the hatred of a heavily indebted population was turned. Tensions rose to the point where, in 1345, the city elite, led by the Bishop of Strasbourg, united to prevent anti-Jewish pogroms. Yet only three years later, at the height of the plague epidemic known as the Black Death, Jews were accused of poisoning wells, and on 9 January 1349 many of them were burned in a special wooden building on an island in the Rhine. It is hard to believe, but already in 1372 a Jew named Joset was appointed the city physician and received not only fees from patients but also a regular salary from the municipal authorities. In the Middle Ages, Jews were forbidden to live in Basel, but, as with any rule, exceptions were made. Thus, Abraham Braunschweig was granted special permission to reside in the city as a proofreader of the Bible published in 1619 by the König printing house.

Relations between Basel and its Jews continued to develop in fits and starts, if one may put it that way. They were expelled and then readmitted, until in 1862 Jews finally acquired the permanent right to reside in the city. On 14 January 1866, as the result of a nationwide vote, Swiss Jews obtained the right to choose their place of residence freely throughout the country, and in 1874 the Federal Constitution definitively enshrined the principle of equality for all citizens, regardless of religious affiliation. (It is now clear why Charles Lewinsky begins his narrative precisely from this period!) In 1897, Basel hosted the First Zionist Congress, held in the city casino, on the site of which a concert hall stands today. One of the Congress’s leading participants, Theodor Herzl, gave his name to a street where the Jewish cemetery, opened in 1903, is now located.

Alas, the oldest Jewish cemetery, first mentioned in the city chronicles of 1264, was destroyed in 1349. Medieval gravestones made of red sandstone were later used in the construction of a granary (Kornhaus), and later still were incorporated into the city’s retaining walls. Excavations in 1937, and again in 2002 and 2003, revealed parts of this medieval burial ground. The earliest gravestones retrieved date back to 1223. Today they are displayed at the entrance to the Jewish Museum of Switzerland in Basel (Jüdisches Museum der Schweiz), which is the subject of this article.

Founded in 1966, the museum became the first Jewish museum in the German-speaking world after the Second World War, and it remains the only one of its kind in Switzerland. The museum’s website explains that the initiative came from members of the Espérance (Hope) burial society, who visited the exhibition Monumenta Judaica in Cologne and discovered that many of the ritual objects on display there came from Basel’s Judaica collection. They concluded that these objects ought to be presented permanently in Basel. At first, the newly established museum occupied only two rooms in a house at 8 Kornhausgasse, the street named after the very granary mentioned earlier. But on 30 November 2025, the Jewish Museum of Switzerland opened its doors at a new location, 5 Vesalgasse. The association supporting the museum’s activities signed a long-term lease for this building, constructed in the nineteenth century as a tobacco warehouse.

The building, which adjoins the site of the medieval Jewish cemetery, is made of wood. I wondered whether there might be a symbolic connection to the wooden structure in which local Jews were burned in the mid-fourteenth century. It turned out there is not, but there is another link.

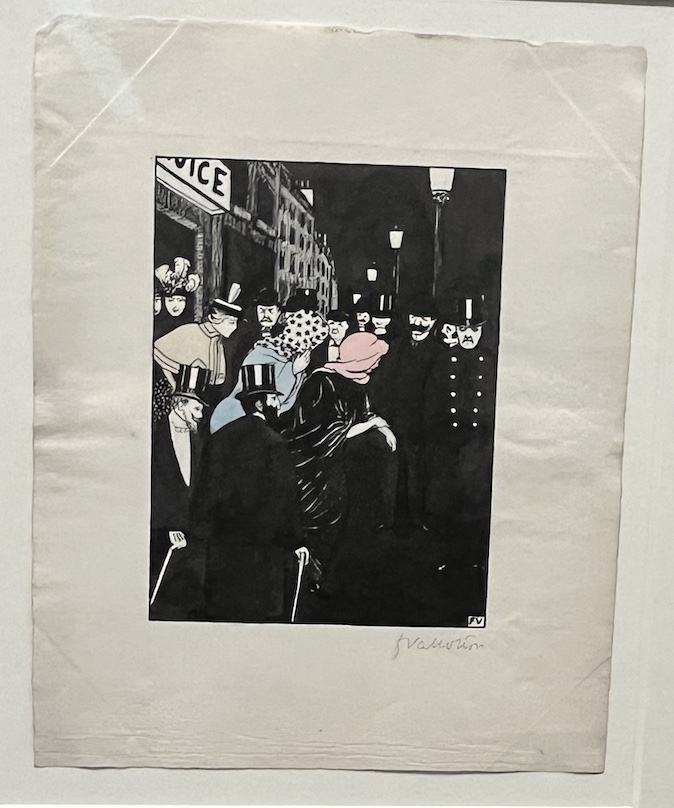

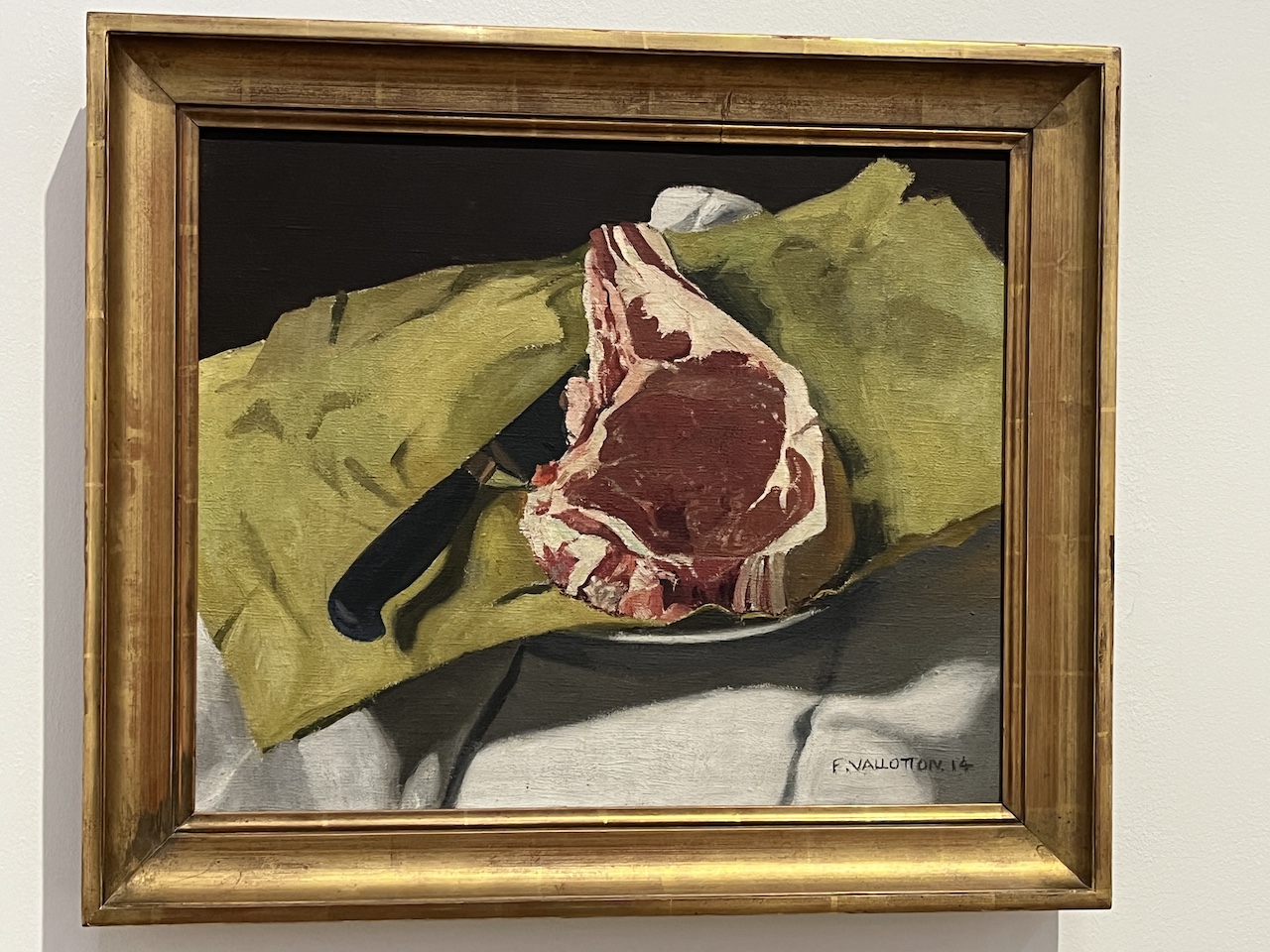

The museum’s façade is adorned with a vivid image that is unlikely, for most visitors, to be associated with the too often tragic history of the Jewish people. Yet those familiar with Jewish symbolism will immediately recognize in it the symbol of life, one of the key values in Jewish culture. The author of this highly original work is the American artist Frank Stella (1936–2024), and its title is Polish, Jeziory, a name common among Polish villages. The reason is that in the early 1970s Frank Stella created a series of collages, maquettes, and monumental reliefs entitled Polish Village (1970–1973). The works refer to around seventy Eastern European villages with magnificent wooden synagogues, where Jewish communities gathered and prayed from the seventeenth to the twentieth century. Almost all of these synagogues were destroyed in pogroms, by fire, during the First World War, and finally by the Nazis.

Frank Stella drew his inspiration for this series from a book by the architect couple Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka, Wooden Synagogues (in Polish: Bóżnice drewniane, 1957). It contains pre-war photographs and sketches of the destroyed synagogues, along with information about the former communities, on which the American artist based his work. And he was not the only one. In Israel there lived a man named Moshe Verbin, born in the Polish town of Sokółka in 1920, who emigrated to British Mandate Palestine at the age of sixteen. Having received a copy of Wooden Synagogues as a gift, he recreated in miniature the synagogues of his childhood. These unique and deeply moving works of art, along with various versions of Stella’s reliefs, are on display at the Basel museum until the end of January 2027, so you have a full year to see them.

“The museum signed an official agreement with Frank Stella granting permission to reproduce his creation on a scale dictated by the architecture of the building. It is a great pity that he passed away in May 2024 and did not live to see how beautifully it turned out,” the museum’s president, Nadia Guth Biasini, told me. By the way, she is an heir to the famous Brodsky family, still remembered in Ukraine for its entrepreneurial activity and philanthropy.

Architect Roger Diener succeeded in transforming the fragile building, protected as a cultural heritage monument, into a museum without compromising its originality. A wide wooden staircase connects all the exhibition floors and creates an open vertical space, where the exhibition Cult, Culture, Art. Jewish Experiences is installed. It presents the history of Judaism in Switzerland from Roman Antiquity to the present day. On the first floor, “Cult” explores Jewish community life and religion. On the second floor, “Culture” presents Jewish history, focusing on the diversity of traditions, autonomy, and survival.

This small building could not have housed a significant part of the museum’s rich collection if the architects had not devised a way to expand the space. They did so by installing pull-out drawers beneath each display case. Pull out a drawer, and you will discover a treasure! “Treasure” is no exaggeration.

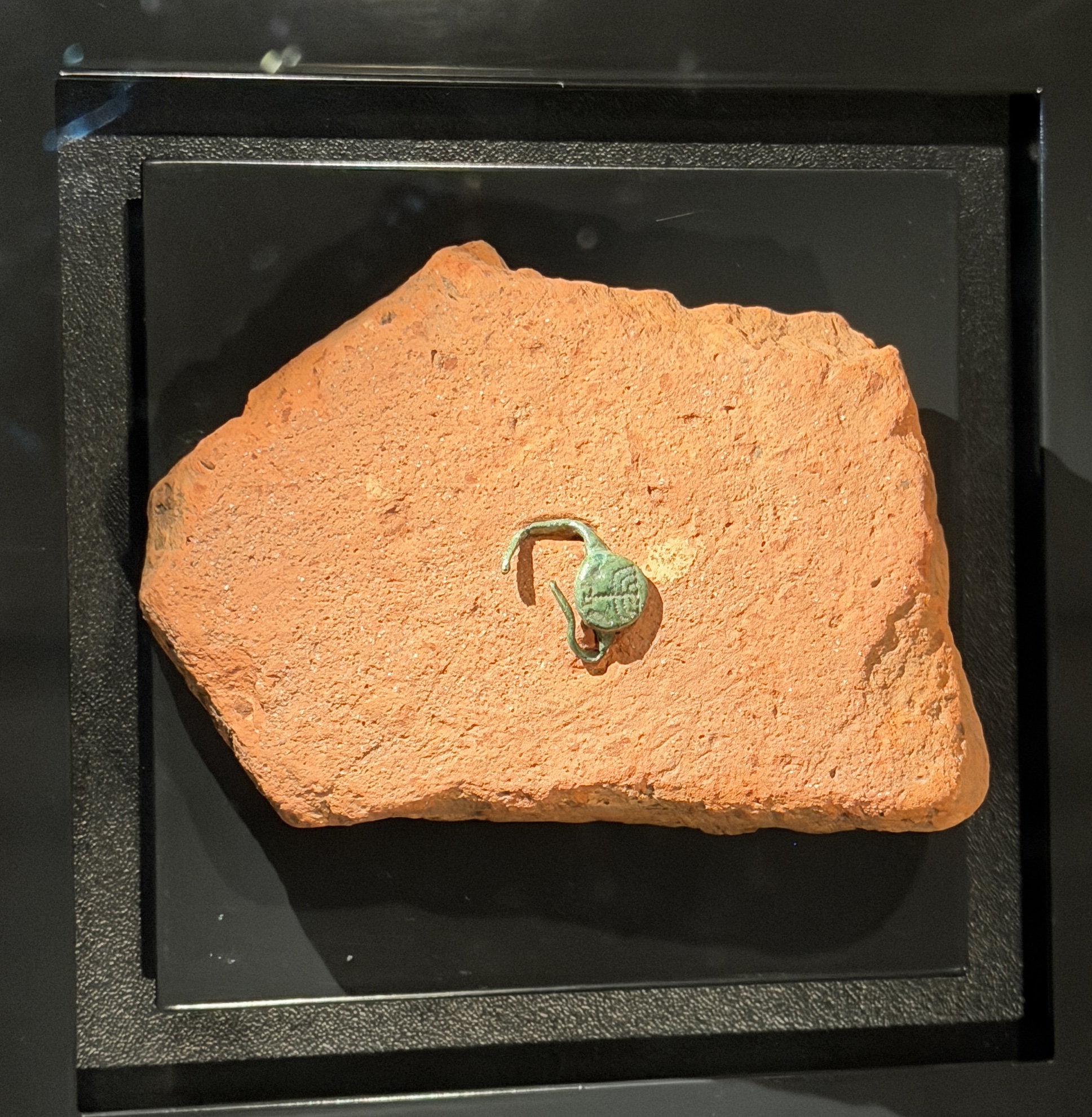

The most valuable of these treasures is a ring from the Roman colony of Kaiseraugst near Basel, on which a menorah (the Jewish lampstand), an etrog (citron), and a lulav (palm frond) are engraved. Discovered during excavations in 2001, this ring is the oldest Jewish artefact found on the territory of modern Switzerland, dating to the years 300–400. In the museum it is kept not only in a separate display case, but also under specific temperature and humidity conditions.

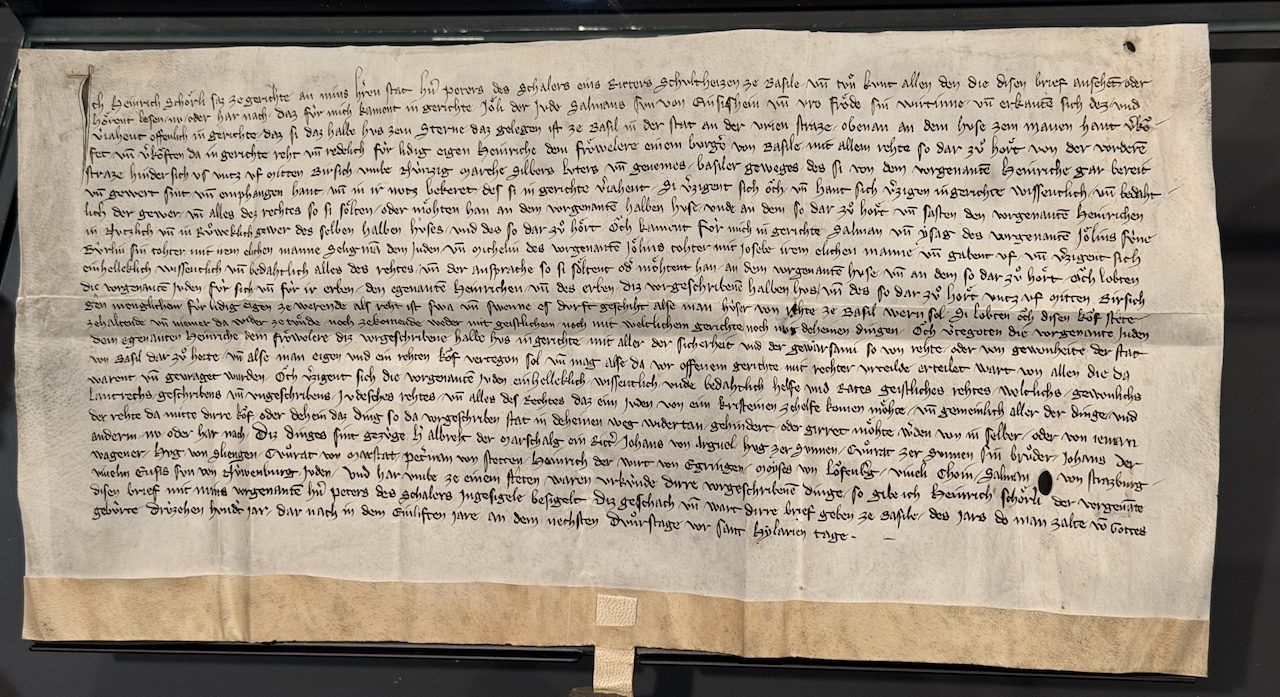

And what about a house sale contract dated… 1311, when Jews and non-Jews lived side by side? That year the Jewish couple Jöli and Fröde sold their half of the house “zum Stern” on Freie Strasse to the Basel citizen Heinrich von Fröweler, undertaking to refrain from any legal action concerning property rights to it, as this historical document attests.

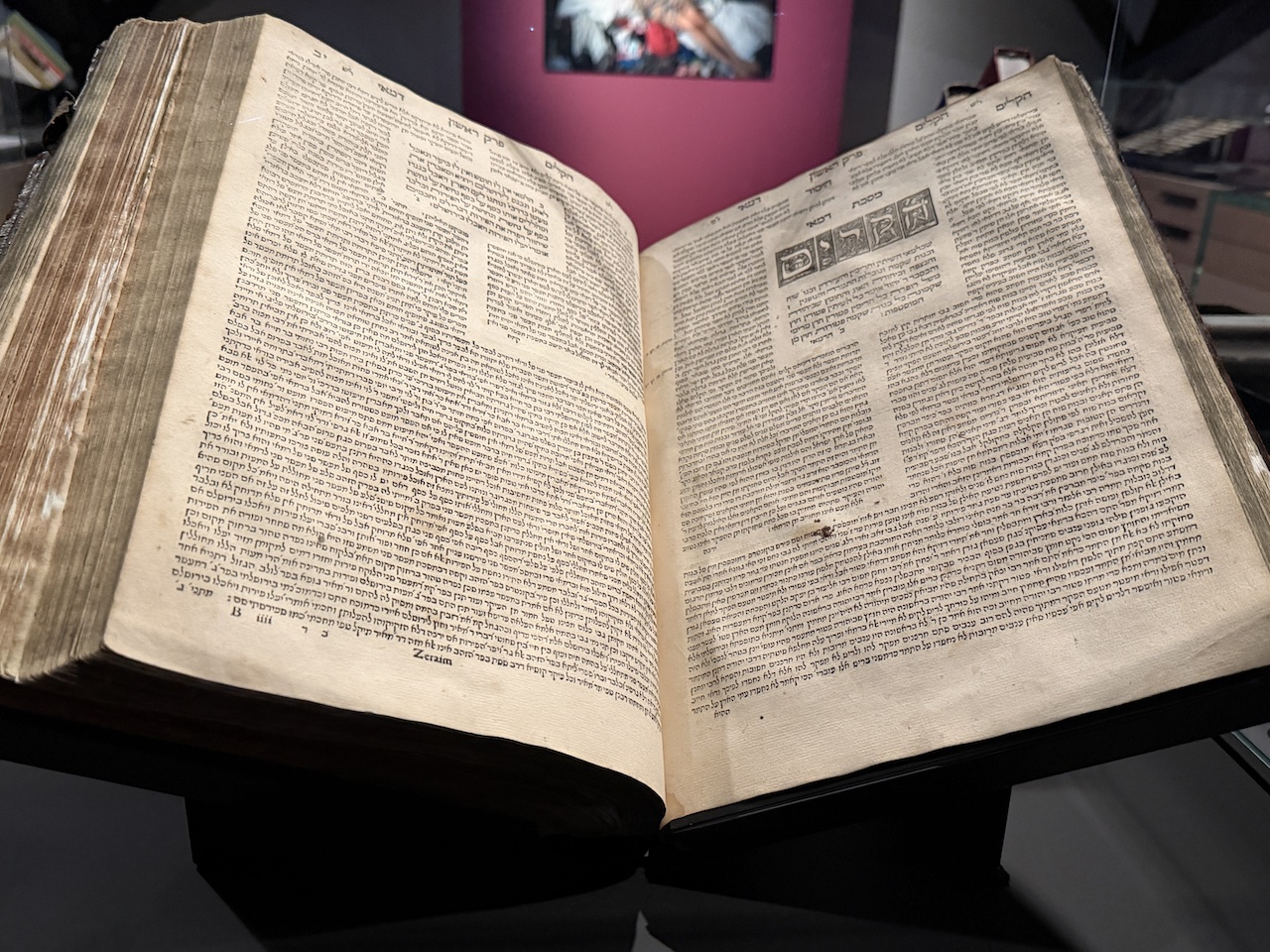

Moving forward in time, we come across a weighty folio. In 1553, Pope Julius III ordered thousands of copies of the Talmud to be burned. Twenty-five years later, Simon Günzburg of Frankfurt approached Ambrosius Froben in Basel with a request to print a new edition. The Basel Council and university professors approved the publication of a censored version, despite opposition from Emperor Rudolf II. Between 1578 and 1580, 1,100 copies were printed, including the one on display here. It combines pages printed in Basel with those from the 1522 Venetian edition, which escaped destruction by fire.

Closer to our own time is another document that calls for explanation. In 1892 and 1893, Swiss animal welfare societies campaigned for “a ban on slaughter without prior stunning”. The campaign was directed primarily against Jewish ritual slaughter, connected with the rules of kashrut (kosher dietary laws), in which the animal is slaughtered without being stunned beforehand. The popular initiative that was adopted drew on antisemitic sentiment. For several years, the canton of Aargau, home to a large Jewish population, granted an exception allowing ritual slaughter, but a draft circular issued by the Aargau cantonal police, provided to the Basel museum by the Zurich State Archives, announced the cancellation of this exemption. Incidentally, the ban on ritual slaughter remains in force in Switzerland to this day.

There are, however, other, more positive historical testimonies. The universities of Bern, Geneva, Fribourg, and Zurich were among the first to open their doors not only to women, but also to Jews, who were admitted without restrictions and with no quotas. Many commemorative plaques, including in Basel, recall Jewish students, among them Chaim Weizmann. Born in the Russian Empire, the first president of Israel, whose name is now borne by one of the world’s leading research institutes, received his doctorate in chemistry from the University of Fribourg in 1899 and in 1901 took up a position as a lecturer in biochemistry at the University of Geneva, where he worked for three years.

There is much more of interest at the Jewish Museum of Switzerland. You will find all the practical information here. And if you have any questions, a member of the museum staff, Artem Istomin, who arrived from Ukraine a few years ago, will be able to answer them, including in Russian.