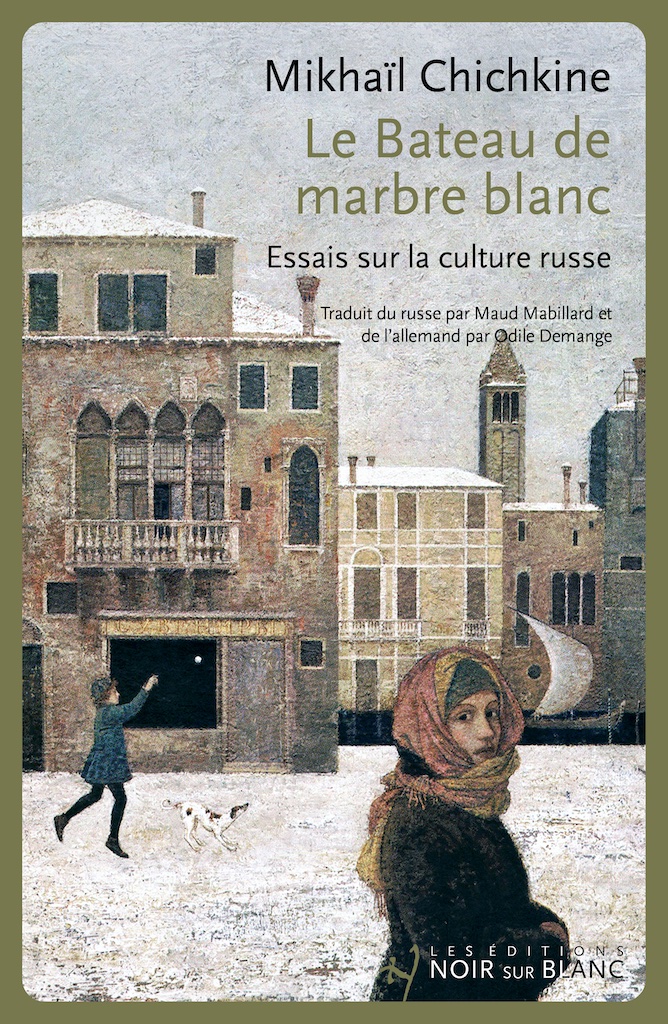

This question is at the heart of Mikhail Shishkin's new collection of essays, The White Marble Boat, recently published in French by the Lausanne-based publisher Éditions Noir sur Blanc and available in bookstores in Switzerland, France, Belgium, and Canada.

Mikhail Shishkin's new "French" book is original in its form, as it is not simply the translation of a work previously published in another language, but rather a collection of texts written in different languages, at different times, and published in different places. Thus, the text titled The White Marble Boat, which gives the book its name and serves as a preface, was first published in the collection Dom ("The House") in Saint Petersburg in 2021. Like an opera overture, it sets the tone by alluding to the various themes that the listener (the reader) will encounter later: "Literature is a loser. Even the greatest books don't make the world better by an iota. (...) Great Russian literature is a great loser." In an essay as touching as it is personal dedicated to the writer Vladimir Sharov (1952-2018), the image of the white marble ship is also explained: "Sooner or later, we come to understand: no sacred truth is contained in any word, and there is only one ship, immense, without lights or crew, that carries us away one after another." Death. And it is on this ship that Russian culture sails, according to the author. Followers of Mikhail Shishkin's work will agree that such statements are not new for him recently; they will discover in this new collection a number of déjà read ideas and a confirmation that the writer's state of mind is not becoming any less pessimistic.

A large part of this new edition consists of nine of the ten essays devoted to Russian writers (the text on Dmitri Ragozin was not included) published in Russian in 2024 by BAbook under the general title Mine with the following subtitle: "Essays on Russian Literature." The text on James Joyce was previously published in 2019 on the Colta.ru website; the text titled "The Russian Ouroboros" was published on the "True Russia" website in January 2023. Seven other texts – no longer just about literature, but about Russian composers and the principles of the Russian soul – were written by Shishkin in German and, to my knowledge, have not yet been published in Russian. Consequently, in the French edition, the original subtitle was replaced with "Essays on Russian Culture." Having read part of the texts in the Russian original and another part in the French translation from German, I was able to try to evaluate them from the perspective of readers with different historical and personal experiences, as well as different mentalities – thanks to translators Maud Mabillard and Odile Demange.

I think that divergences of perception will begin from the very first page, or rather from the epigraph which uses a quote from Mikhail Shishkin himself, opening with this question: "What is wrong with the world created by Cyrillic?" The Russian-speaking reader will either agree or be indignant, while the non-Russian speaker may perhaps try to apply this question to their own world, created by the Latin alphabet: is everything fine at home?

Reading these pages, the cultivated reader, not necessarily Russian-speaking, will recall Vladimir Nabokov's famous lectures on Russian literature; lectures prepared, as we know, for students at Cornell University and other American universities. Mikhail Shishkin does not establish a parallel with Nabokov; yet Nabokov is present in his texts with surprising frequency and in the most diverse ways – from quotations of works to suppositions about what his great predecessor would think or say. One thus has the impression that the two writers are linked by a special relationship. At least on Shishkin's side.

Another thing. The French-speaking reader approaching this book will certainly not grasp the reference made by the author to the essay by poet Marina Tsvetaeva titled My Pushkin. In the collection Mine, Mikhail Shishkin's texts are titled, by analogy, "My Pushkin," "My Dostoevsky," "My Chekhov," and so on. In the French edition, however, these same titles have been replaced by others, more elaborate. On the other hand, every reader will understand and feel deep within that this book is written by a man undergoing profound moral suffering, who questions everything and everyone; a man overwhelmed by emotions and who struggles to overcome their waves. This is why it is difficult to evaluate this collection in which purely literary essays alternate with very personal confessions and texts that closely resemble political pamphlets.

One may disagree with much of what Mikhail Shishkin writes in this book; particularly with what seems to me to be contradictory. By giving numerous examples of how good literature has helped people survive in the most dramatic circumstances (the account of Anna Akhmatova and James Joyce is quite interesting in this sense) and how one can remain a decent person and do one's work honestly, even under a totalitarian regime ("He knew he was being used to demonstrate the human face of a slave empire, but he also knew that his music helped slaves to live," he writes about Dmitri Shostakovich), Shishkin arrives, in the Russian-language edition, at the following conclusion: "All my life, I felt solid ground under my feet, and it was Russian culture. Now, under my feet, there is emptiness." Well, how come –emptiness? All these authors whom Mikhail Shishkin speaks of with so much love, even when he criticizes them for certain positions that displease him; all these geniuses of Russian culture for whom he does not hide his admiration have not disappeared anywhere. One need only take their books from the shelf, listen to their music, to enter into dialogue – even into debate from which perhaps truth can be born.

In this collection, many take a beating: the Orthodox Church, the Russian people as a whole and "the progressive intelligentsia" in particular, Western Slavicists, thick literary journals, Switzerland where Mikhail Shishkin has lived for thirty years already... Many readers will certainly be shocked and consider these remarks as proof of gross ingratitude. Yet the author has the right to have his own opinion, and I will not contradict him.

At one point, Mikhail Shishkin writes that throughout its history, Russia has known only two states: order or the time of troubles. Let us apply this equation to a person whose "order" (peace of mind, of soul) has been replaced by spiritual turmoil caused as much by an understandable rejection of the injustices raging all around, as by awareness of the limitations of one's own means to overcome it. In Mikhail Shishkin's soul, as in that of many of my compatriots, this turmoil reigns today, this sensation of having lost one's footing, of treading water and self-destructing; and it is not for nothing that the last essay included in the French collection is titled "The Russian Ouroboros." However, in my opinion, worse than turmoil, more terrible than turmoil, there is only indifference; and the author certainly cannot be accused of this sin.

This is why, if the fate of Russian culture interests you, I recommend reading this work. To compare your own thoughts and feelings with those expressed by Mikhail Shishkin.

P.S. A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to see, at the A. Griboyedov Russian Theatre in Tbilisi, a wonderful production of Anton Chekhov's "Uncle Vanya," directed by the very young Georgian director Nika Chikvaidze, born in 1992. The program quotes his words: "Does happiness exist? And if it exists, where is it located? People resemble passengers on a ship doomed to destruction, because they forget that happiness lies in small things, in self-love. The characters, prone to self-destruction, involuntarily destroy everything around them: forests, their fellow humans, themselves... They forget the profound meaning of human life: to do good. To be useful and indispensable to at least one person, in order to justify one's own existence." There too, the image of the ship. But one wants to believe that the course it has taken depends at least a little on the captain.