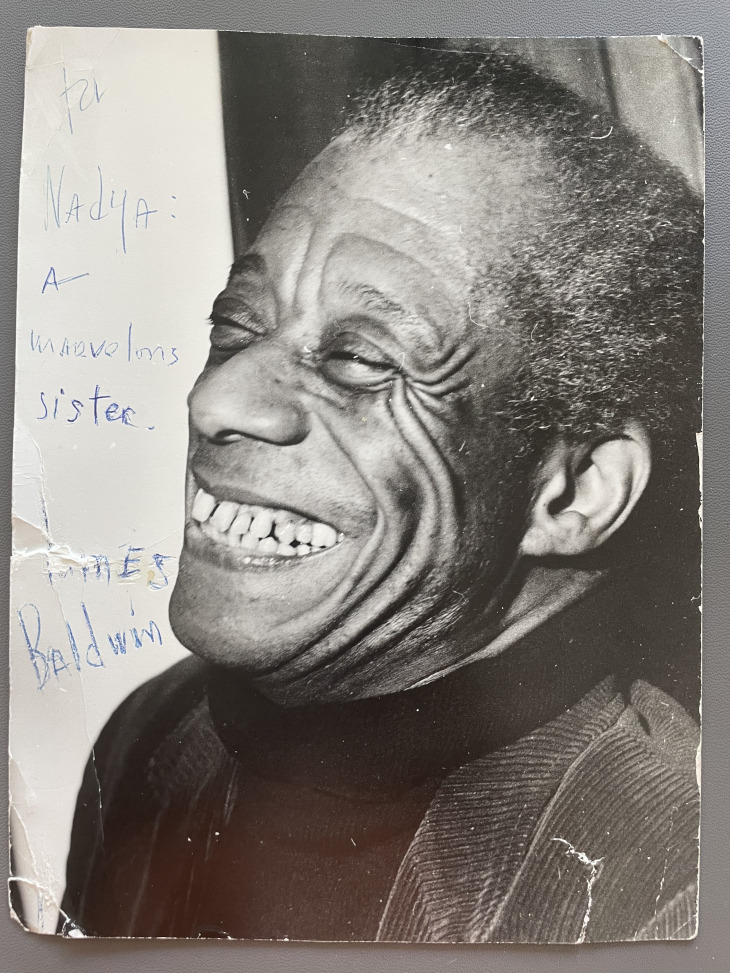

The multitude of people one meets in life can easily be divided into two groups: those who lift us up and those who drag us down. The first group outweighs the second, and the earlier we choose it, the more interesting and fulfilling our existence becomes. In my youth, I had the incredible fortune of meeting many exceptional people who influenced me. James Baldwin is one of them.

In March of this year, the Federal Service for Combating Racism (SLR) released a report in which it acknowledged for the first time the existence of systemic racism in Switzerland, in several areas. This awareness now calls for concrete actions and perhaps partly explains the decision by the Kunsthaus in Aarau to organize an exhibition on the subject of racism, built around the African-American writer James Baldwin (1924-1987); he is considered by many participants in the "Black Lives Matter" movement as their ideologue and spiritual leader - even if they don't always quote him accurately.

If this author and his work are unfamiliar to you, know that James Arthur Baldwin was born on August 2, 1924, in the Harlem neighborhood of New York, and died on December 1, 1987, in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, in the French Alpes-Maritimes. He never knew his biological father and was raised by an adoptive father, David Baldwin, a pastor. James, the eldest of nine children in a very poor family, thought he would follow his father's example and become a pastor himself, but as he grew older, he realized that David Baldwin's sermons reflected neither the reality of Harlem nor his own behavior at home. Having finished school in the Bronx, James moved to Greenwich Village and began his literary career. It may seem surprising, but he started his apprenticeship in world literature with the works of Dostoevsky; his very first published text was an article on a Soviet writer Maxim Gorky, which appeared in the American weekly The Nation in 1947.

James Baldwin's writings draw their inspiration primarily from his own diverse and multiple experiences. His credo was simple and clear: "to be an honest man and a good writer." He achieved both objectives by using his personal impressions to paint a picture of the reality surrounding him. From his first texts, readers sensed the power of a tribune ready to dedicate his life to the fight against all forms of racism – this theme is the leitmotif of his work.

It was not easy being black and homosexual in 1940s America. Baldwin joined the glorious brotherhood of prophets rejected by their country: as soon as the opportunity arose, specifically in November 1948, the author moved to Paris where he would write his major works. Since then, he returned to the United States only twice. During the second visit, in summer 1957, he met – in Atlanta, Georgia – Martin Luther King, whose movement he actively supported and whose ideology he shared. For his first trip in June 1952, he had to borrow money from Marlon Brando, but the importance of this trip was considerable: James Baldwin was going to New York to present the manuscript of his novel Go Tell It on the Mountain to Knopf Publishers. Baldwin received $250 as an advance, then another $750 when the revised manuscript was accepted for publication. I give all these details because this crucial moment in James Baldwin's life has a direct connection to Switzerland.

It so happens that he had completed this first novel during the winter of 1951-52 in the village of Leukerbad (Loèche-les-Bains), in the Swiss canton Valais, where he had spent three months in the family chalet of his friend Lucien Happersberger, a young Swiss photographer with whom Baldwin, according to his biographers, had fallen in love in Paris the previous year. The love, however, was not reciprocated. The writer would later become godfather to Lucien’s and his wife Suzy's son; and the two men remained friends until Baldwin's death. But in 1952, back in France, he wrote, based on the impressions from his stay in Leukerbad, the essay Stranger in the Village, which served as the starting point for the exhibition currently presented in Aarau.

There's no need for me to tell you the content of this essay. I hope you will read it and agree with me when I say that in this twelve-page text, James Baldwin reveals not only his talent as an essayist, but also as a philosopher, a profound analyst, and a keen observer equipped with an excellent sense of humor. After provoking the greatest curiosity among the inhabitants, he in turn ironizes about the customs of the Valaisans. The tone is set from the first sentence: "From all available evidence no black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came." Then he continues: "It did not occur to me – possibly because I am an American – that there could be people anywhere who had never seen a Negro. It is a fact that cannot be explained on the basis of the inaccessibility of the village. The village is very high, but it is only four hours from Milan and three hours from Lausanne." This is the remote corner where James Baldwin found himself: "In the village there is no movie house, no bank, no library, no theater; very few radios, one jeep, one station wagon; and, at the moment, one typewriter, mine, an invention which the woman next door to me here had never seen." On the other hand, there is a Ballet Haus - "closed in the winter and used for God knows what, certainly not ballet, during the summer."

The story takes place in winter, and the author observes, with sincere interest, how "in the middle of this white wilderness, men and women and children move all day, carrying washing, wood, buckets of milk or water; sometimes skiing on Sunday afternoons."

James Baldwin is no less amazed by the village's main attraction – the hot spring water. Or rather by the public they attract. "A disquietingly high proportion of these tourists are cripples, or semi-cripples, who come year after year – from other parts of Switzerland, usually – to take the waters. This lends the village, at the height of the season, a rather terrifying air of sanctity, as though it were a lesser Lourdes."

As for the villagers' attitude toward "the stranger," their curiosity manifests itself in multiple ways that James Baldwin summarizes thus: "In all of this, in which it must be conceded, there was the charm of genuine wonder and and in which there was certainly no element intentional unkindness, there was yet no suggestion that I was human: I was simply a living wonder." But not for everyone: while some villagers willingly drank a glass with him in the evening and offered to teach him how to ski, others accused "le sale nègre – behind my back – of stealing wood."

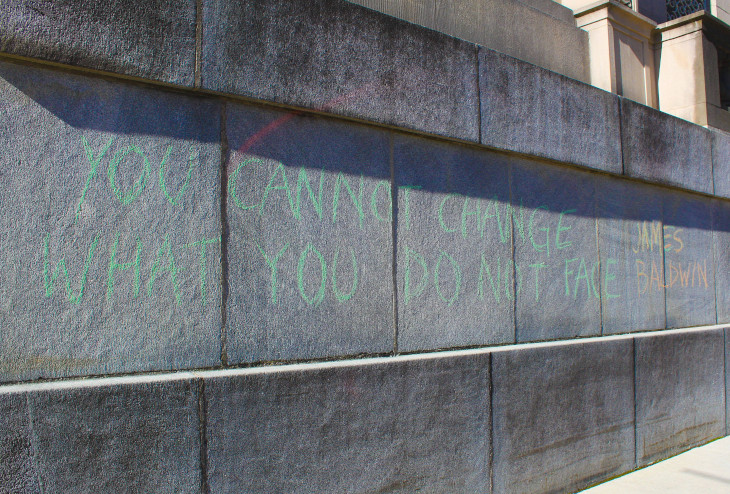

James Baldwin's reflections on the differences in the perception of black people in Europe and in his native America are very interesting, as are those on the difference in the perception of reality by people of different races even when it concerns places of worship and cultural monuments. "People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction, and anyone who insists on remaining in a state of innocence long after this innocence is dead turns himself into a monster." The conclusion James Baldwin reaches following his stay in Switzerland is harsh and pragmatic: "It is precisely this black-white experience which may prove of indispensable value to us in the world we face today. This world is white no longer, and it will never be again."

I don't know to what extent James Baldwin is known in Switzerland, but I know that Russian-speaking readers know him regrettably little, although as early as 1977, his excellent text Sonny's Blues was published in the USSR in the form of a very small brochure. Baldwin had then been presented as "a progressive American author, a brilliant representative of the Harlem literary renaissance."

Nine years later, in 1986, James Baldwin traveled for the only time to the Soviet Union. This fact is little known: it is absent from his Wikipedia page, and in the biography that concludes the magnificent collection of his writings assembled in two volumes under the direction of Toni Morrison, Nobel Prize laureate in literature, it is mentioned in a single line: "In October, he left with his brother David for an international conference in the Soviet Union." Allow me to add a few details. The international conference in question was the Issyk-Kul Forum, an informal meeting to which Mikhail Gorbachev had invited some illustrious foreigners including Arthur Miller, Peter Ustinov, Alvin Toffler, Claude Simon, each of whom planted a tree in the Kyrgyz soil, on the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul. And I, a second-year university student, had been hired as an interpreter thus having the immense privilege of attending all the discussions of these people who seemed to me to be extraterrestrials.

It was at that moment that I discovered James Baldwin's books, which allowed me to understand not only the profound problems of black people in the United States, to which Soviet citizens were not exposed, but also, strangely, to become aware of the problems of Jews in the USSR, which many of my acquaintances faced daily: we were just emerging from an era when, for example, young Jews were not admitted to the Institute of Theoretical Physics bearing the name of Lev Landau, the 1962 Nobel laureate in physics and himself a Jew. " This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish. Let me spell out precisely what I mean by that, for the heart of the matter is here, and the root of my dispute with my country. You were born where you were born, and faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. I know that your countrymen do not agree with me about this, and I hear them saying “You exaggerate.” They do not know Harlem, and I do," writes James Baldwin to his nephew in The Fire Next Time. One need only replace "black" with "Jewish" and "Harlem" with "item 5" (the section of Soviet passports where "Jewish" appeared as nationality), for the analogy to become apparent.

By the way, The Fire Next Time, one of Baldwin's major texts from which I extracted the passage quoted above, is still not translated into Russian, as far as I know. Why, I wonder? Perhaps because of these few lines concerning the Civil War in Spain? “We defend our curious role in Spain by referring to the Russian menace and the necessity of protecting the free world. It has not occurred to us that we have simply been mesmerized by Russia, and that the only real advantage Russia has in what we think of as a struggle between the East and the West is the moral history of the Western world. Russia's secret weapon is the bewilderment and despair and hunger of millions of people of whose existence we are scarecely aware”.

James Baldwin died from esophageal cancer a year after his trip to the USSR, in his home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, surrounded by his brother David and his best friends – Hassell and Happersberger. A few days before, he had insisted on celebrating Thanksgiving, although he was already too weak to join the guests at the table. The text he was working on at the time, The Welcome Table, remained unfinished...