The dazzling success of Giuliano da Empoli’s first work of fiction has made the press, critics, and – which is rare! – ordinary readers talk about him: more than once I have seen people relaxing in the autumn sun or riding public transport with The Wizard of the Kremlin in their hands. The novel, published in April this year by Gallimard, could not have appeared at a more opportune time. Now, as the whole world follows the course of the war in Ukraine and tries to predict the next move of the Russian president, a book offering a psychological portrait of that figure – “composed” by an insider, Vadim Baranov, whose prototype was Vladislav Surkov, the former chief ideologist of Vladimir Putin’s administration – naturally arouses keen interest. Still, to receive the Grand Prix of the French Academy and be shortlisted for the Goncourt Prize within a single week is an exceptional achievement.

Giuliano da Empoli is a Franco-Italian-Swiss author. He was born in 1973 in the Paris suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine to an Italian father and a German-speaking Swiss mother. He lived with his parents in several European countries. In 1986, Giuliano’s father was the victim of a terrorist attack. Fortunately, he survived, but from then on, the family lived under police protection. Giuliano da Empoli earned a law degree at Rome’s La Sapienza University and a political science degree at the Institut d’Études Politiques in Paris. For many years he worked with Matteo Renzi – first as his deputy for cultural affairs at Florence City Hall, then as political adviser when Renzi became Italy’s prime minister. In 2016 he founded the think tank Volta, part of the Global Progress network.

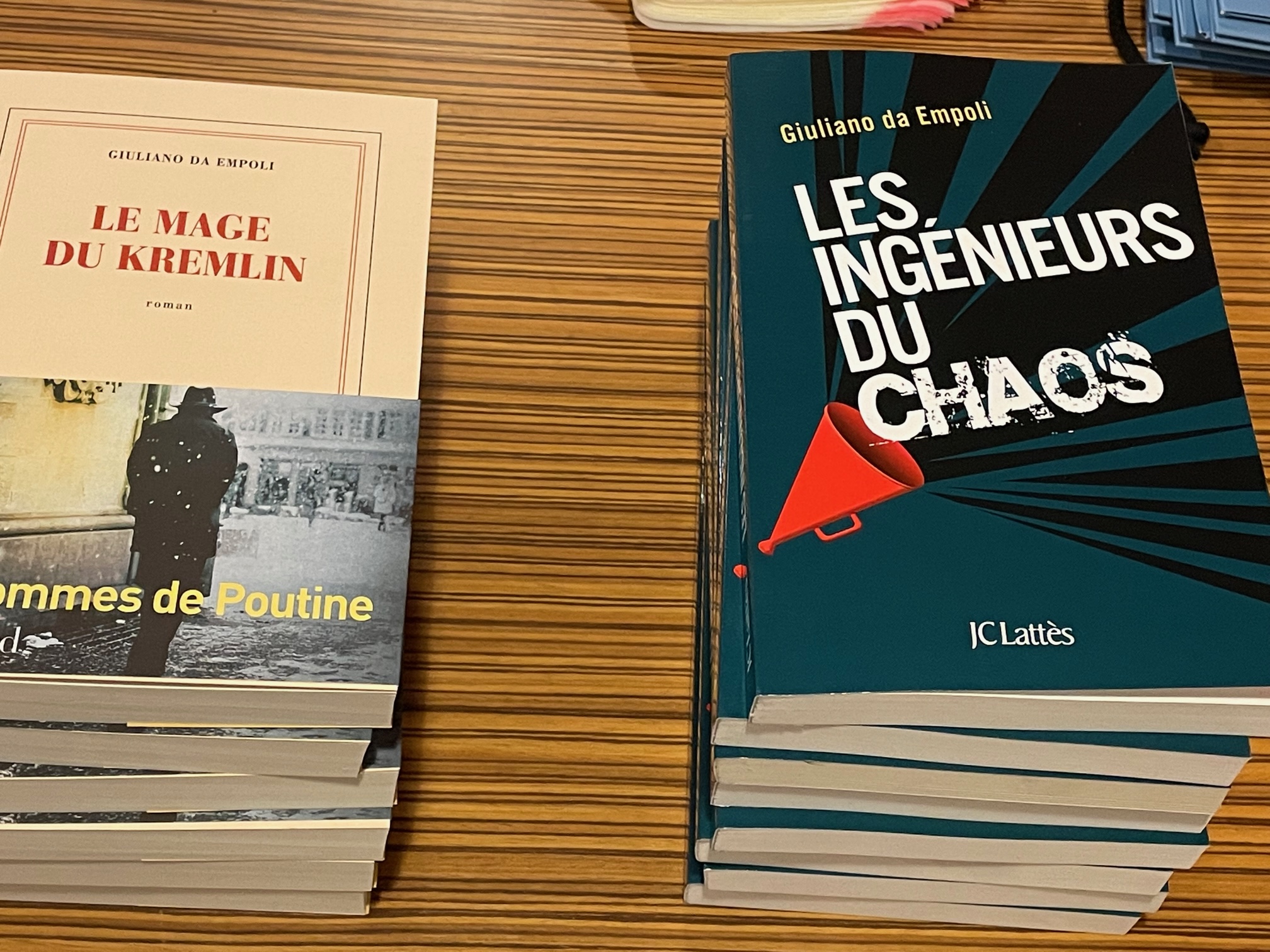

Since 1996, Giuliano da Empoli has been a regular contributor to leading Italian periodicals and hosts a radio program. He currently also teaches at the Institut d’Études Politiques in Paris. At twenty-two he wrote his first non-fiction book, about the difficulties facing Italian youth; it sparked heated public debate and earned him the title “Man of the Year,” awarded by La Stampa. His essay The Engineers of Chaos (Les Ingénieurs du chaos, Lattès, 2019), about the spin doctors among national populists – those public relations specialists whose job is to shape public opinion in favor of particular politicians – was translated into twelve languages. Much of The Wizard of the Kremlin was written in Switzerland, which the author considers the complete opposite of Russia, in his family’s house in Interlaken, where he spent his school holidays as a teenager.

I met Giuliano da Empoli the day after his talk at the Société de Lecture, a true Geneva institution founded in 1818. There were so many people wishing to hear him that the meeting had to be moved from the elegant Louis XV–style mansion in the Old Town to a larger modern hall, and even that was filled to capacity.

Giuliano, first of all, sincere congratulations on your stunning success! Do tell me how did your interest in Russia arise? Have you learned Russian?

I haven’t learned Russian, except for a few words – not even worth mentioning. But I was fascinated by Russia from my very first trip there. That was in 2011, when I was deputy mayor of Florence for cultural affairs, and an Italian film festival was taking place in St. Petersburg and Moscow. I must admit, Moscow impressed me more. On one hand, it almost inspires fear: it’s a city where power is felt in everything, from architecture to people’s facial expressions. And at the same time, there is beauty, softness, tenderness. I’m Italian, I love walking, and in Moscow those walks were very pleasant. I don’t want to revive stereotypes, but the Russian spirit really exists, it touched me then and continues to do so now.

Is it fair to say that The Wizard of the Kremlin is, in a sense, a fictional development of the theme you began in The Engineers of Chaos? After all, here too the main character and narrator is a spin doctor – only a Russian one?

Exactly. To continue using Anglo-Saxon terminology, it’s a kind of spin-off that moves in a different direction, shifting from essay to fiction.

The way you built the narrative mirrors the real distribution of roles: the president, Putin, is constantly discussed but rarely seen, while Surkov–Baranov remains in the shadows, spinning his web. Which of them is the “chief engineer” of chaos?

(smiles) Putin, of course. At the very beginning of the novel, Baranov realizes that all those who thought they could control or manipulate Putin had in fact underestimated him. He understands that he can accompany this figure and even at times suggest important decisions, but Putin has his own trajectory. That is the tragedy of the novel, if you like: in the first part, Baranov is Putin’s fellow traveler; in the second, he gradually realizes that the tsar’s trajectory is rooted in violence – born of it, sustained by it, and destined to end in it. And no one can stop him. Baranov himself does not believe in violence; he thinks the best results come from manipulating public consciousness. That’s where he and Putin diverge.

Why were you drawn specifically to Vladislav Surkov, a figure not particularly well known even in Russia, and much less so in the West, who has also retired from public life? Russia has far more colorful characters.

Surkov is an unusual personality, standing out in Putin’s entourage, made up mostly of rather “gray” former security officers, childhood friends, or judo trainers. Surkov, with his more artistic nature and his view of politics as a theatrical performance, struck me as an interesting fictional character. But it must be emphasized: Baranov is not Surkov; Surkov was only one of the inspirations for the character.

Have you ever met Surkov or Putin?

No, never.

Then how do you know about the samurai statue in Putin’s reception room?

(laughs) I have my sources. The samurai really exists.

In your novel you mix real and fictional characters, or at least those under fictional names. Why did you bring Yevgeny Zamyatin into the story? Do you really believe that we are witnessing the fulfillment of the predictions he made a century ago in his novel We?

Exactly. Zamyatin was an extraordinary visionary. In his time, We was seen as a critique of the emerging Soviet system, but today the book has taken on even greater meaning and should be read as a critique of the modern age. That is the miracle of literature: a century later, some books become more relevant than when they were written. Digitization, total transparency, the collection of personal data on every individual enabling the effective control of society – all this is brilliantly depicted by Zamyatin. For me We is a very important text, and that’s why I wanted to weave it into my novel.

When one reads the quotation from We that you cite, about how “we have nothing to hide or be ashamed of”, a chill runs down the spine because of the similarity. But it’s hard to believe that today’s “Surkovs” are educated enough to use it as inspiration for the “We Are Not Ashamed” posters now hanging in Russian cities.

(laughs) Indeed, that’s hard to believe! Besides, if we’re being precise, Zamyatin’s prediction has been realized “more to the letter” by the Chinese; that’s why, at the end of the novel, I distance myself slightly from Russia. In Russia, total control over the population is still in its early stages; in China, it’s already well advanced.

You include several Soviet-era jokes in your book – back then, that “kitchen genre” thrived. But there seem to be no jokes about Putin. How do you explain that?

That’s something you should explain to me! Haven’t a few appeared since the start of the war? For example, the War and Peace cover replaced by Special Operation and Dried Fish? Of course, these jokes are sad, even when we laugh at them.

Baranov–Surkov’s grandfather philosophizes about life’s unpredictability and tells his grandson: “The only thing you can control is your interpretation of events.” That, in fact, becomes his profession. How do you explain the paradoxical combination of Russians’ complete distrust of power (if television says there will be no shortage of toilet paper, everyone rushes to buy it) with their equally complete obedience to it?

Hmm… again, that’s a question I should ask you. It seems to me the roots of this phenomenon go back to the Soviet period, perhaps even the tsarist era. It’s clear that in the USSR people grew used to the constant use of double language. Remember the old joke: “We pretend to work, and you pretend to pay us”? That was a situation in which no one believed in the official system and its rhetoric; they only pretended to, since they believed even less in the possibility of an alternative. The system’s support was not people’s faith in it or their enthusiasm, but their cynicism, their inertia. Of course, there are those who genuinely support Putin’s regime, but I think they are fewer today than before. That doesn’t mean the curve couldn’t rise again. Most of the population remains passive, partly because they no longer know what to believe. Even since the war in Ukraine began, how many different versions have been offered as to why it was needed and what its goals are?

You give a very sharp definition of the “new Russians” when you write: “The Russian elite is united by a shared impoverished past that each of its members had to endure before reaching villas on the Côte d’Azur and bottles of Petrus.” It’s hard to imagine a more scathing description. Do you despise these people?

Not at all. I gave that definition to explain the “new Russians” to Western readers, who often misunderstand who they are. Those we call “new Russians” – people who made huge fortunes in the past thirty years – are the first generation of the wealthy. In the West, such nouveaux riches are mixed with heirs to fortunes in their second, third, and later generations. In Russia, there are very few of those, perhaps a few descendants of the old nomenklatura, like Baranov himself: his grandfather an eccentric minor nobleman, his father a typical apparatchik. Having inherited something “by birth,” Baranov observes the circus of the new Russians with irony and distance.

Can the behavior of the “new Russians,” including the president himself, still be explained by a deep-seated inferiority complex?

Undoubtedly. That’s often the case among people who strive for power and achieve it. They have a particular psychology, often rooted in some trauma, some old wound. And that’s dangerous, because one can hardly ever heal from such a wound or complex: no matter how high such people climb, at some point they can derail.

When the war in Ukraine began, many expected that the oligarchs, deprived of their “toys”, would rebel. But they didn’t, and probably won’t. Would you say your statement, “The only real privilege in Russia is closeness to power. That privilege is the opposite of freedom – it’s a form of slavery,” explains why?

The portrait of the oligarchs has changed over thirty years. The first ones, who made their fortunes in the 1990s thanks to proximity to power, actually held that power in their own hands. Putin’s arrival marked a radical shift in the balance of forces: those who tried to resist him were eliminated one way or another, and the rest accepted the new rules. Today, despite their differences, they are united by service to the “tsar,” knowing perfectly well that otherwise the punishment would be harsh.

“The sole purpose of power is to respond to people’s fears.” That’s frightening. Do you mean power in a totalitarian state, or power in general?

I think in general. The very idea of the state was born from the fact that, faced with certain dangers, people were willing to submit to authority if it would protect them. Otherwise, they would live without rulers or rules. A totalitarian state pushes this submission to the extreme, but even in our democracies, the state comes under threat when people feel unprotected from crime, economic crises, or climate risks. It’s in such moments that protest movements arise to challenge the authorities.

Your novel emphasizes the negative aspects of Boris Yeltsin and the damage he did to Russia’s image. Why then does Putin never say a bad word about him, while he insulted Gorbachev both in life and after death?

He had a pact with Yeltsin. As far as I can tell, Putin’s logic resembles that of a mafioso – he observes certain agreements. He promised not to touch Yeltsin in exchange for power, and he kept that promise. With Gorbachev, there was no agreement. Putin, like many Russians, believes Gorbachev was responsible for the collapse of the USSR.

The topic of Russians’ inexplicable submissiveness whose origins are sought not only in the Soviet past but in serfdom and Orthodoxy, is now widely discussed. You yourself write: “The tsar restored the vertical of power in Russia, and voters are grateful to him for it.” And Berezovsky declares in your novel: “You are serfs, for generations!” Could it be something genetic that makes Russians a unique people who don’t want freedom, not even the most basic choice?

No, of course it’s not genetic. But the facts are there. In Russian history there’s a pattern of rebuilding the vertical of power and submission to it. Although many Russians took offense at certain passages in Marquis de Custine’s notes on Russia in 1839, they were accurate, especially about subservience and inertia. The street scene he describes, where a coachman lashes the crowd to clear the way for a carriage, and people fall under its wheels while others look on indifferently, is hard to imagine today, but that trait does exist among Russians – not in their genes, but in their political culture, which is very hard to change. Still, that doesn’t mean there’s no hope or that things can’t change. But it will take a lot of work.

You mentioned Marquis de Custine. As you know, his hugely popular book was banned in Russia for fifty years. Do you expect your novel to be translated into Russian in your lifetime?

(laughs) That depends on how long my lifetime will be. But I’m superstitious, so I won’t make predictions. Clearly, not anytime soon.

“The Soviet Union didn’t lose the Cold War. The Cold War ended because the Russian people freed themselves from the regime that oppressed them.” This statement, made by Putin in your book, is, on one hand, key to understanding his politics, and on the other, contradicts it since Russia is now returning by giant steps to that same dark past.

You’re absolutely right, that is the tragedy of Putin’s regime. Russia is returning to its starting point. When he came to power, Putin promised to restore order and did so with brutal force –we all remember what happened in Chechnya. Today this course of harshness and violence has reached its peak. The contradiction lies in the fact that, having promised order and stability, he has now broken that promise by destroying order. Those Russians who believed him now find themselves in a state of chaos, uncertainty about the future, growing isolation. That, I repeat, is the real tragedy.

You write that “the Labrador is the only adviser Putin fully trusts.” Seriously, is there anyone in his circle who still maintains a link with reality?

That Labrador is gone. But seriously, I think Putin is increasingly isolated. There are people who, for a time, enjoy his trust, but only for a time. He constantly sets those around him against each other, forcing them to compete: the Kremlin’s “power struggles” are visible even beyond its walls.

If you were Putin’s adviser, what way out of the current dead end would you recommend to him?

I’m afraid it’s too late to advise Putin on anything, and is there anyone who could influence him? I don’t think so. What would I advise him, given that reality is so different from what Russian television shows? Obviously, I’d tell him to try to find a symbolically acceptable way out, but essentially, to end the war. But I doubt he would heed such advice.

Is it still possible today to love Russia?

That’s a difficult question requiring a long answer. It’s hard to love Russia today, since it would be naïve to believe that the war now raging is solely Putin’s war. We must avoid two mistakes. On the one hand, it’s wrong to say Putin is merely a victim of circumstance – he’s not. On the other, it’s wrong to think that once he’s gone, everything will be fine. It won’t. The ongoing war has once again forced us to confront something that exists in Russian society and that to us, in the Western world, seems terrifying: violence. But can that call into question not only our love for Russian culture, which is obvious, and its place in European and world culture, which is undeniable, but also our love for all that is good and beautiful in Russia?

I can give you only my personal answer. I’m very sad that in the foreseeable future I won’t be able to go to Moscow. I miss it; I feel nostalgia, and that means love still lives. I agreed to this interview because I wanted to speak with you after reading your article in which you write that you understand the feelings of those Germans who were against Hitler. It reminded me of Klaus Mann, Thomas Mann’s son, who wrote about the same thing: leaving Germany with his parents in 1933, he found himself in a Paris café where everyone looked at him with suspicion because he was German, and therefore an enemy. Your words touched me deeply, and I want to express my sincerest sympathy.

Thank you very much!