In order to attend the press preview of the new exhibition and to enjoy it, if not alone, then at least among similarly privileged visitors, I did not hesitate to leave Geneva at 6:30 a.m. To my surprise and disappointment, when I arrived at the museum five minutes before ten, I found an impressive queue already forming at the entrance. Journalists were admitted separately, but this did nothing to reduce the number of visitors in the galleries. There was no traditional press conference either; instead, a video address from the museum’s director, Sam Keller, was circulated. Perfectly fine, of course, but not quite the same. A pity, since journalists, as we all know, have a particular fondness for exclusivity.

I can’t say that the exhibition struck me as particularly original in its concept. Nevertheless, the pleasure was undeniable. And how could it have been otherwise? The exhibition brings together close to 80 works by the master born in Aix-en-Provence, including 58 paintings and 21 watercolours, and focuses on the late and most significant period of his career. Part of the works on display come from private collections, while the rest are treasures from the Fondation Beyeler itself, complemented by major loans from leading museums around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and Tate in London.

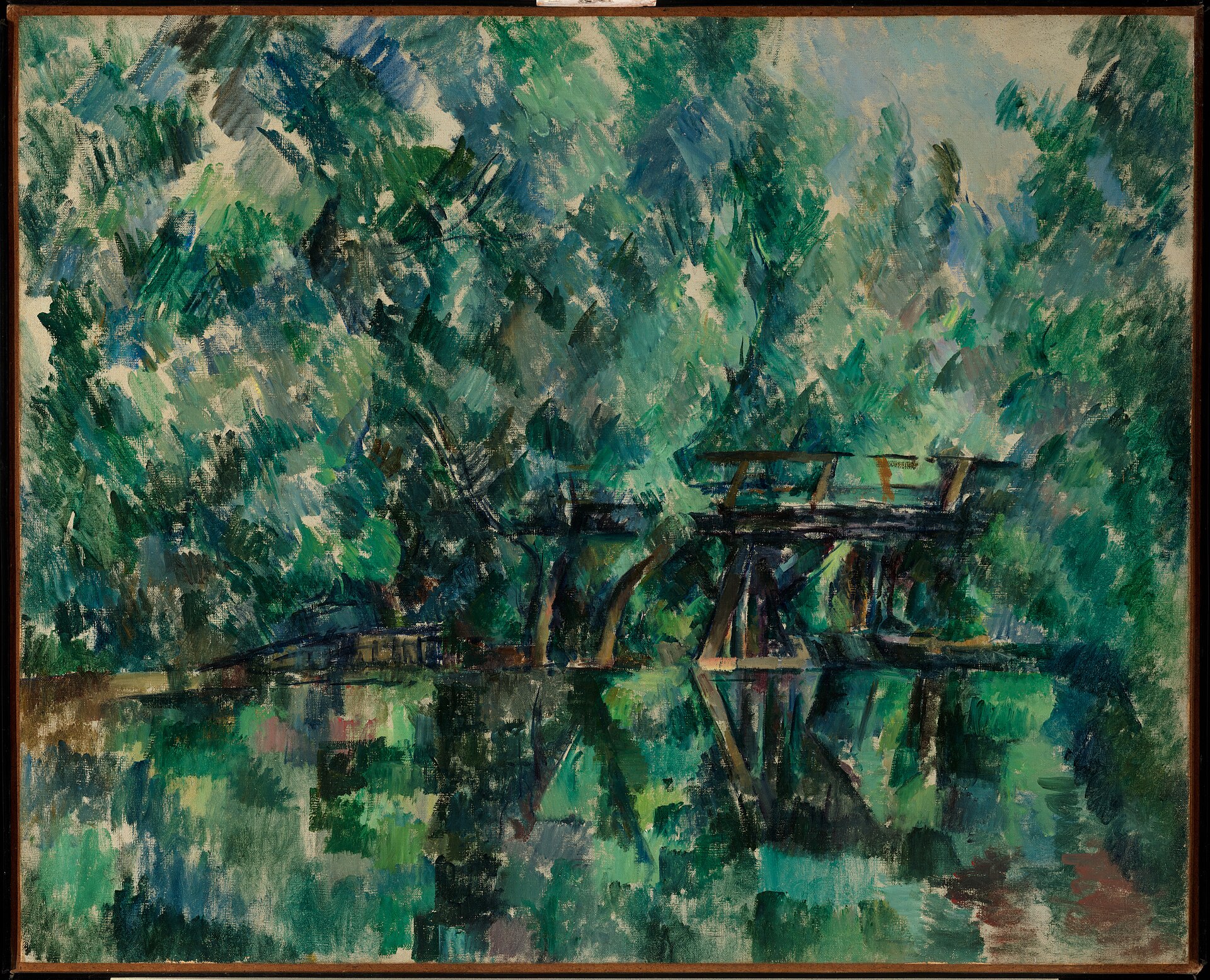

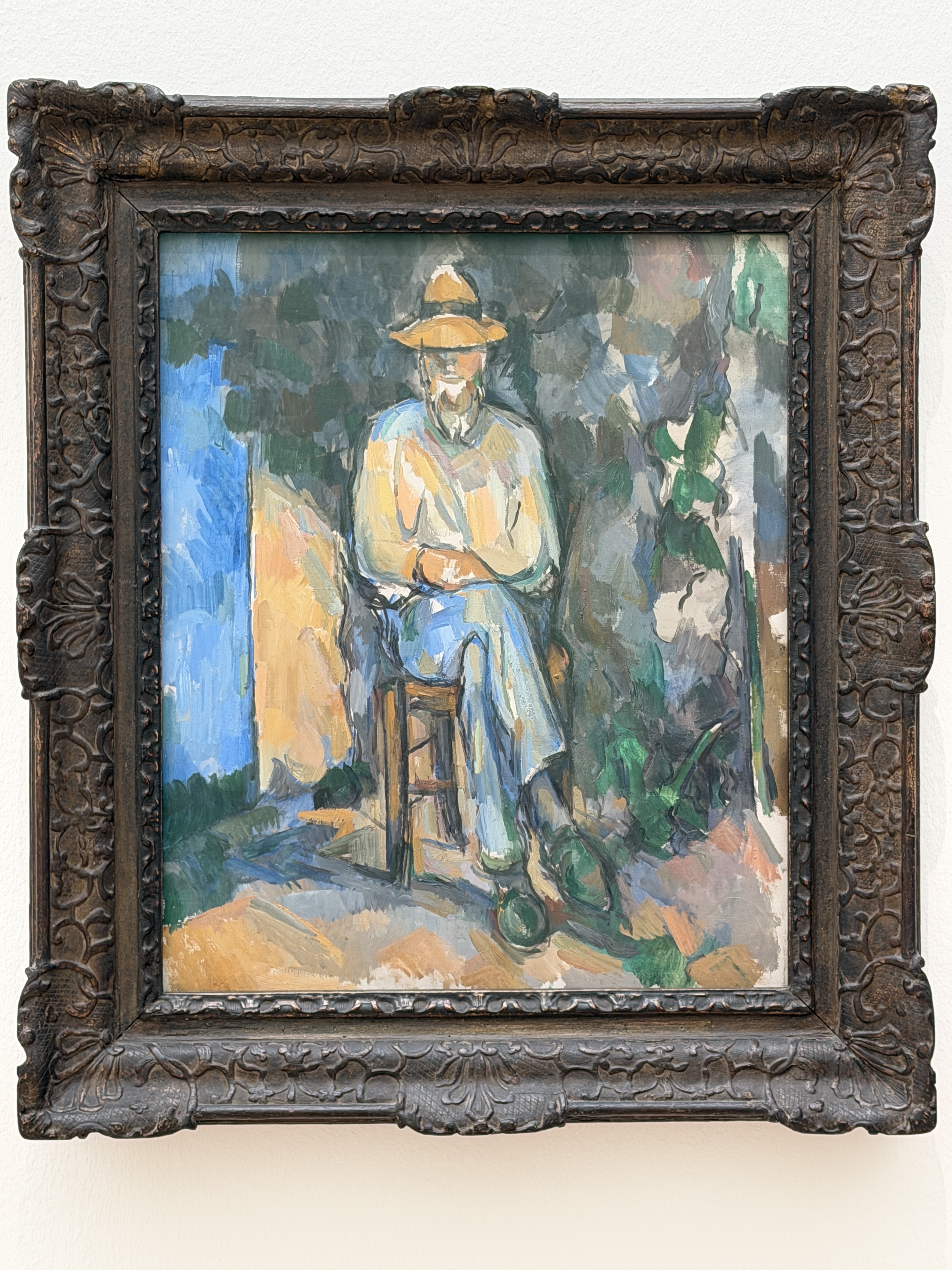

Here is everything that has shaped our fondness for Cézanne: enigmatic portraits, idyllic figures of bathers, Provençal landscapes of deeply sensuous expressiveness. Chronologically, the exhibition begins in the mid-1880s. By that time, Cézanne had already freed himself from the influence of Impressionism and developed his own distinctive style, liberated from traditional conventions such as central perspective or anatomically accurate representation. Cézanne’s declared ambition was not to reproduce nature as such, but to analyse and render visible in painting the very process of perceiving the natural world. In his studio in the south of France, he entrusted himself fully to intuition, seeking to capture and fix the interplay between light, colour and form, while concentrating on a limited group of motifs that would become central to his work, above all the landscapes of his native Provence.

Moving from one gallery to another at the Fondation Beyeler, one initially has the impression that the exhibition offers variations on a small number of themes. By and large, this is indeed the case. Visitors can, for example, compare nine (!) views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, located in southern France near Aix-en-Provence. Considered part of France’s natural heritage and protected as such, the mountain takes its name from the victory of Gaius Marius over the Cimbri and Teutons in 102 BC. Its worldwide fame, however, is owed to Cézanne.

“Again and again, he set up his easel before this rocky massif, seeing in it an ideal testing ground for the central question that preoccupied him: how to paint the world as it is truly perceived. For Cézanne, this meant not simply depicting nature, but showing its forms, its colours and its atmosphere, art as a parallel to nature. From the 1880s until his death, he painted Mont Sainte-Victoire around thirty times in oil and produced numerous watercolour views of it,” explains the exhibition’s curator, Ulf Küster.

The Fondation Beyeler presents seven of these paintings and two watercolours, revealing the artist’s laboratory, in which he transferred pure “colour sensations” onto the canvas by means of “patches of colour”, striving to create form through colour alone.

The exhibition also offers a rare opportunity to see, side by side, two exceptional versions of The Card Players (1893–1896), one from the Courtauld Gallery in London and the other from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, as well as two watercolour versions of Boy in a Red Waistcoat (1890–1891). Fourteen still lifes with fruit are also included. At first glance, these paintings may appear to be simple arrangements of apples, pears, oranges, jugs, pitchers, loaves of bread and carefully draped tablecloths. In reality, they constitute a field of sustained experimentation with form, colour and balance.

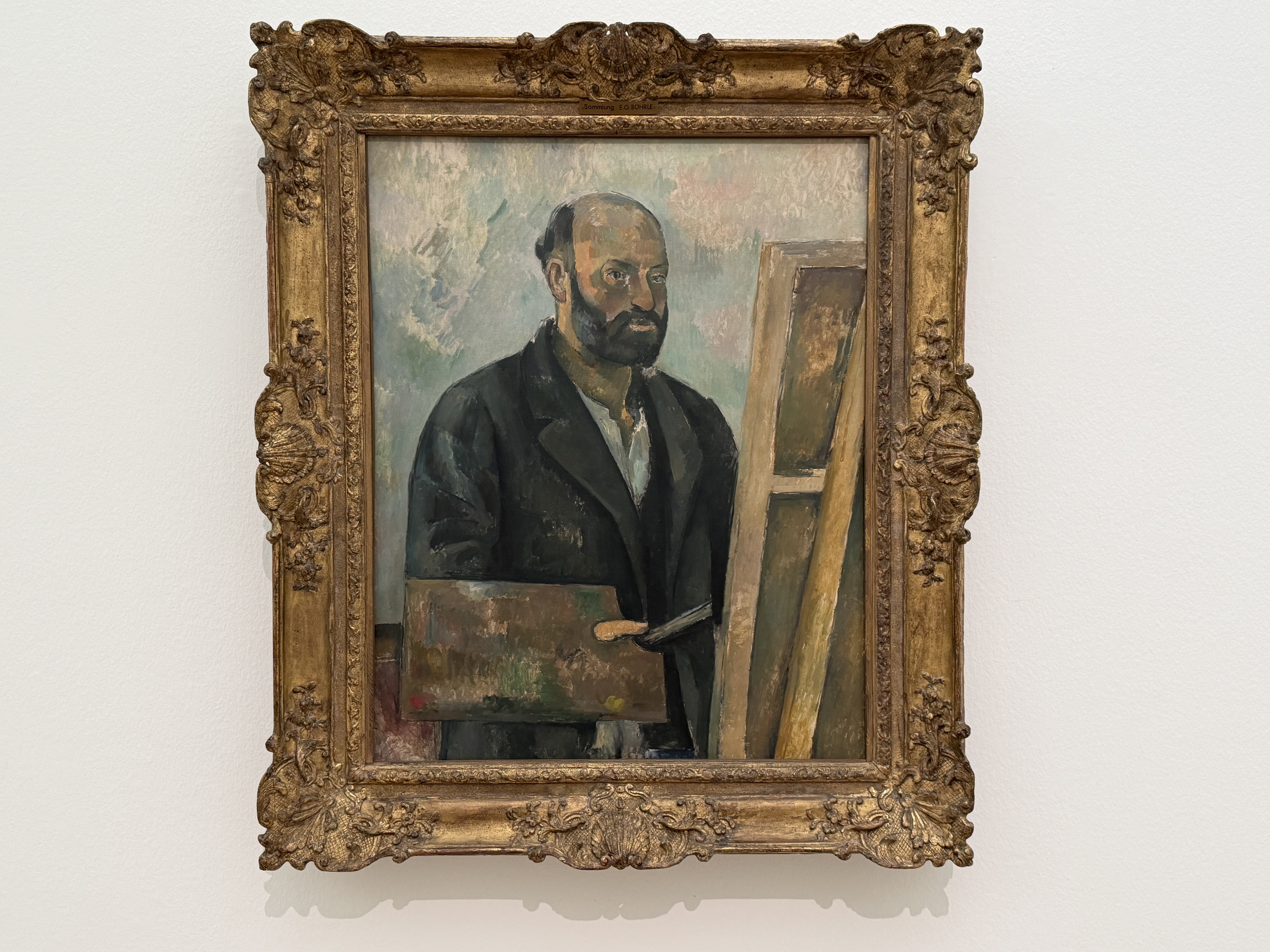

Equally compelling are the eight portraits and self-portraits, among them the Portrait of Paul Cézanne of 1895, which remained unseen by the public for decades. Special attention should also be paid to The Millstone in the Park of the Château Noir (The Millstone), painted between 1892 and 1894. Brought to Basel from Philadelphia, this major work is being shown in Europe for the first time. A separate gallery is devoted to images of bathers, female and male, a subject to which Cézanne returned repeatedly, each time proposing new variations and exploring the relationship between the human body and nature.

Of particular interest are works that appear unfinished, with certain areas of the canvas left blank. This is, of course, no oversight, but a deliberate choice by the artist, who opted for such an “open ending”, allowing viewers to engage their imagination freely.

Against the exuberant colours of landscapes and fruit, paintings featuring skulls may at first seem dissonant. They nevertheless reveal the philosophical dimension of Cézanne’s work, as he reflected, like any great artist, on questions of life and death.

Yes, the exhibition is excellent, without question. And yet I could not help missing other works by Cézanne that have been familiar to me since my childhood. In Russia, divided between the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow and the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg, there exists a substantial collection assembled at the beginning of the twentieth century by the patrons Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin. It includes, among other works, the celebrated Pierrot and Harlequin and The Large Pine, an entire series of views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, numerous bathers, and many still lifes. It is no secret that Paul Cézanne exerted a fundamental influence on the Russian avant-garde of the early twentieth century, laying the foundations for “Cézannism” among the artists of the Jack of Diamonds group, which included Pyotr Konchalovsky, Ilya Mashkov, Aristarkh Kuprin and Robert Falk. In 1998, the Pushkin Museum hosted a remarkable exhibition entitled Cézanne and the Russian Avant-Garde. One can only regret that visitors to the Fondation Beyeler will not see the works shown there, and hope that this absence will prove temporary.

P.S. If you are unsure whether to visit the exhibition, a quick look at my small photo gallery should put your doubts to rest.