Enchanted Fiennes and Coffee with Lensky

Interest in the production was immense from the outset. Tickets for all performances were sold out well before the premiere, and in this way the Parisian public responded to the debate about whether Russian culture should be cancelled, a question repeatedly raised against the backdrop of the ongoing war in Ukraine. I say this without any triumphalism, merely as an observation. The director’s name undoubtedly contributed to the excitement as well. Ralph Fiennes is indeed a celebrated actor, and rightly so. One need only recall his roles in Schindler’s List, The English Patient, the Harry Potter series, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Spectre, and many others. His fascination with Russian classics is beyond doubt. In interviews he often speaks of being enchanted by them, explaining that Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev is his favourite film. Fiennes himself played Onegin in the film directed by his sister Martha, Ivanov in Chekhov’s play at London’s Almeida Theatre, which was later presented on the stage of Moscow’s Maly Theatre, Alexander Pushkin in his own film The White Crow, and Rakitin in Vera Glagoleva’s adaptation of Turgenev’s A Month in the Country. I therefore expected no hidden agenda from him. I was, however, slightly disappointed to see on the vast panel adorning the façade of the Palais Garnier, that brilliant example of Second Empire eclecticism blending Baroque, Classicism and sheer decorative splendour, not the familiar faces of Alexander Sergeyevich and Pyotr Ilyich, but an advertisement for Bottega Veneta. Аfter all, someone has to pay for the renovations.

According to Stanislavsky, theatre begins with the cloakroom. The contemporary spectator, however, often keeps their coat and instead begins their theatrical experience with the programme booklet, which sets the interpretative frame of the performance. Thus anyone who purchased the programme for Eugene Onegin was immediately initiated into a “secret” that had long been concealed from Soviet audiences, from the publication of Nina Berberova’s novel Tchaikovsky in Berlin in 1936 until its long-delayed publication in Russia in 1997: the great composer was homosexual. “The composer was writing the work at the very moment he was enduring a painful marital failure, the result of a marriage entered into solely to conceal his homosexuality.” I will not speculate on the significance of this fact for the creation of Eugene Onegin, yet I cannot quite understand why the programme devotes such emphasis to it, given that Fiennes’s staging is not built around a queer reading.

It is worth noting that the same passage in the programme highlights another, no less important point: “Even more striking is the novel’s ominous echo of Pushkin’s own death. In his verses, the character of Lensky dies in a duel at Onegin’s hand, only a few years before Pushkin himself, Russia’s greatest poet, succumbed to wounds sustained in a duel triggered by a romantic quarrel.” One cannot help noticing that the fact that Pushkin’s killer was the Frenchman Georges Charles d’Anthès, and that the duel was prompted by rumours concerning his relationship with Pushkin’s wife Natalia Goncharova, is discreetly omitted. As I discovered, not everyone is aware that Pushkin died in a duel, and sometimes even the singers performing Lensky’s role do not know it! Without the slightest irony, I must add that the programme booklet, a substantial volume, is assembled with great professionalism and care. One need only mention the essay Tchaikovsky and “Eugene Onegin” by Isaiah Berlin, which, I am convinced, will prove a revelation for music lovers of many nationalities and help them better grasp the hidden meanings of both great works, the literary and the musical.

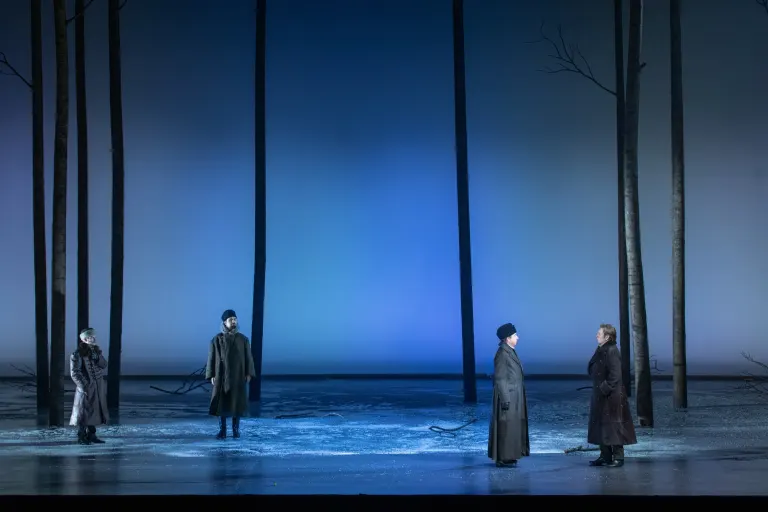

What can be said about the production itself? To be honest, not so much. My long-time readers know that I belong to the old school, respect tradition and approach directorial inventions with a certain caution, especially when Russian repertoire is concerned. Yet even I was surprised by how classical this staging turned out to be, with its minimalist scenography, apart from the ballroom scene in St Petersburg: a few birch trees, or perhaps aspens, on the stage and curtain, a table, a garden bench… Ralph Fiennes truly managed not to deviate from the original plot by a single step and avoided making even the slightest reference to current events. His thorough knowledge of the literary source of Tchaikovsky’s opera becomes evident from the very first moments of the performance. At the back of the stage, strewn with fallen autumn leaves, in a beam of light the audience sees not the titular hero Onegin but Tatyana, often regarded as Pushkin’s favourite heroine. In his novel in verse, as he himself defined the genre, the author openly admits in Chapter Three, “I am so in love with my dear Tatyana…”, and indeed his sincere tone whenever she appears sharply contrasts with the ironic colouring that often accompanies Onegin.

As always, I tried to watch this performance both from my own Russian perspective and through the eyes of a foreign spectator. The latter might have been surprised by the sudden transformation of the young men dancing at the ball in Act Three into bears. I would venture to suggest that in doing so Ralph Fiennes sought not to portray “Russian aggression”, for he is far too enchanted by Russia for that, but to incorporate into the stage action Tatyana’s famous dream from Chapter Five, which usually remains outside the dramatic frame. In that dream, Tatyana walks through a winter forest pursued by a bear, which carries her across a stream and leads her to a strange hut where Onegin sits among monsters. Lensky appears there as well, and the dream ends with a scene foreshadowing the future duel. Traditionally, critics explain the importance of this dream by noting that it includes a caricature of high society. Some interpret the bear as a masculine archetype, a brute force of destiny guiding Tatyana toward inevitable disillusionment.

There is also something here to reflect upon, even at the risk of calling down thunder and lightning upon my own head. If one looks closely, Tatyana, having read too many novels and languishing in boredom, herself endowed the visiting guest with all the traits of an ideal hero and fell in love not with a real person but with an image she had created. Can Onegin be blamed for failing to live up to that image, when he did not take advantage of the young girl’s trust and returned her compromising letter instead of reading it aloud to his friends, that is, in today’s terms, instead of posting it on social media, which by modern standards is almost heroic?Alas, romantic natures prone to self-enchantment nearly always encounter the collapse of their illusions. Do pay attention to the conversation between Madame Larina and the nurse at the beginning of Act I, when Tatyana’s mother speaks of habit as a substitute for happiness, echoing Pushkin’s line “Habit is heaven’s gift to us: a substitute for happiness,” and concludes that there are no heroes in life. Interestingly, in Pushkin’s text these lines belong to the authorial narration, whereas in Tchaikovsky’s opera the composer and the librettist Konstantin Shilovsky place them in Larina’s mouth, thus reinforcing the contrast between the dreamy Tatyana and the pragmatic experience of the older generation. Yet do we ever listen to the older generation?! Tatyana, unlike other heroines of Russian literature, neither drowned herself nor threw herself under a train; instead, she married a mature, self-assured man who not only regained “both youth and happiness” but also surrounded her with the love and respect she unquestionably deserves. As for Onegin, who admits “I was so wrong”, well, he is punished enough.

What, then, unsettled me personally? Three things. The appearance of the Larins’ peasant girls (“Lovely maidens, gentle friends…”) in kokoshniks à la the Beryozka folk dance ensemble, together with the characteristic gliding movement associated with that same ensemble, but here performed by society ladies and having little to do with either the polonaise or the écossaise at a St Petersburg ball. I was also surprised that in the final scene between Tatyana and Onegin the “queen of the ball” appears almost in a nightdress: even if, in Onegin’s eyes, she has become “the former Tatyana” again, for everyone else, and for herself, she has changed profoundly and would hardly have received him in such undress. Onegin himself might have thought twice before moving from humble supplication to the commanding “you must belong to me” had Tatyana been dressed in a manner befitting her new social status. If one accepts that Pushkin loves a strong Tatyana who never loses her dignity, then something essential is lost here. Yet these directorial details are trifles against the exceptionally high musical level of the performance, which is, of course, what matters most.

The orchestra under Maestro Semyon Bychkov is impeccable. Born in Leningrad in 1952, he graduated from the Leningrad Conservatory in Ilya Musin’s conducting class. It is know that, while still a student, he conducted Eugene Onegin twenty times at the Conservatory Opera Studio, earning two roubles and fifty kopecks for each performance. I am sure this “return to the source” brought him genuine pleasure, all the more so since the Palais Garnier is now to become his “home”: earlier this year Semyon Bychkov was appointed music director of the Paris Opera.

I have no complaints whatsoever about the Armenia-born soprano Ruzan Mantashyan as Tatyana, nor about Elena Zaremba, a Muscovite, as the nurse Filippyevna. The graduate of the St Petersburg Conservatory Boris Pinkhasovich is also very good in the title role, although I would note the occasional exuberant gesticulation that does not quite fit the image of a cold Onegin. True to himself is Alexander Tsymbalyuk, a graduate of the Odessa Conservatory, as Gremin. The only performer who, in my modest opinion, falls out of an otherwise well-balanced ensemble is the Maltese mezzo-soprano Marvic Monreal, who sings Olga.

Yet I looked forward most of all to meeting Lensky – I have particularly high standards when it comes to tenors. And what a pleasure it was to hear for the first time Bogdan Volkov, born in the Donetsk region, a graduate of the National Music Academy of Ukraine, who went through the Young Artists Opera Programme at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre and was named “Singer of the Year 2025” by the German magazine Opernwelt! This is a true Lensky, just as he ought to be. Unexpectedly, I had the chance to meet him, even though for several days now I have been plagued by guilt that, for the sake of our encounter, the lyric tenor stepped outside into pouring rain.

It so happened that a week before the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, Bogdan Volkov left Moscow to take part in Daniel Barenboim’s production of Don Giovanni at the Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin, which turned out to be the last operatic project of the great maestro. Since then, Bogdan has been living in Europe, moving from one theatre to another; his workload is colossal. I would like to share with you the most interesting, in my view, excerpts from our conversation, as a continuation of my personal impressions of the performance I saw.

Bogdan, every “Russian” production in Europe provokes a storm of emotions, often negative ones. Did you encounter anything like that in Paris? What has it been like working here, both in general and specifically with Ralph Fiennes? How well does he understand music?

Personally, I did not encounter anything negative, and I think nothing of the sort happened. On the contrary, many positive reviews were published. The work went wonderfully; Maestro Semyon Bychkov helped us greatly with the music, and overall, a very friendly, trusting, almost family-like atmosphere developed. We all communicated in English, though Ralph Fiennes would sometimes insert a few words in Russian. There was no sense that he was someone who had never staged opera. After all, he has worked as a director in drama theatre and in film, and that is a field that brings together several disciplines; dramatic directors often work with opera singers as well. The approach is more or less the same: working on the character, the inner world, sensations, reactions, motivations. Everything therefore unfolded naturally.

This is not your first Lensky. What do you think of Ralph Fiennes’s interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s opera, his choice in favour of absolute classicism?

I do not know how to measure the concept of classicism. Probably everyone imagines a classical work differently after reading the book; it depends on one’s imagination. I understand that the production may seem classical at first glance, and at the very first rehearsal Ralph Fiennes said that we were, as it were, in Pushkin’s era, but this is not about historical illustration, nor about fanatically observing every historical detail. He especially emphasised that we, the performers, should move with complete freedom, like people of the twenty-first century. So, we worked a great deal on being natural and free. As Larina sings, “We are neighbours, no ceremony between us.” And so you can put your hands in your pockets, sit on the table, because everyone around you is familiar, the atmosphere is domestic, almost homelike. Lensky visits the Larins almost every day; he feels at home, and he has brought his best friend, who is received just as warmly: make yourselves at home, sit down, do whatever you like. All this immediately goes beyond the idea of a so-called classical production.

How did the director introduce you, so to speak, to the atmosphere of Russia in the first half of the nineteenth century?

At the first rehearsals he brought printouts of paintings by various nineteenth-century artists, showing people in relaxed, everyday situations: someone writing a letter, someone tired, someone lying on a bench, reading something, resting. I especially liked the portrait of Ilya Repin’s son Yuri, where he stands with one hand tucked into his coat, against a winter backdrop. It resembles an illustration of the duel scene, and for me that is Lensky. When creating my character, I sometimes borrowed these gestures and symbols. There are also other episodes in the production in which I do not participate, so I cannot explain them in detail, for example that surreal dance when the hussars turn into bears.

I explained that dance to myself as Tatyana’s dream.

Perhaps. Or perhaps it is something wild, a kind of choreographic interaction between the masculine and the feminine. In any case, when it came to Pushkin, Ralph Fiennes was prepared one hundred and fifty percent. For every idea he would find a quotation in the poem. At times Maestro Bychkov suggested placing something slightly later or slightly earlier, relying on the musical texture and pointing to an important moment in the score that could underline a particular state or action. So, it was a genuine collaboration between director and conductor.

Although Ralph Fiennes was thinking about Pushkin’s time, the production seems almost outside time, were it not for two or three hints…

Europeans are far less familiar with Pushkin’s work than, for example, with Chekhov. On the other hand, in opera, as Stanislavsky used to say, one must not illustrate the text but interpret it. Many composers wrote operas about the periods contemporary to them, which sometimes led to scandals, as their works provoked contradictory reactions. Opera must evoke emotions, different from those experienced when watching a documentary or historical film.

Any great work is the result of inspiration experienced by the author and of deep reflection on the events that concerned him. La Traviata, Eugene Onegin, and many other operas were written about people contemporary to their creators. It does not matter when we watch or listen to them; what matters is that we live through the same emotions as the composer and thus become his contemporaries. So it does not matter whether a production is staged in a modern, futuristic, or retrospective key. What matters is that it is justified and resonates with us today.

What is the relevance of Onegin today?

That is for the audience to decide. When I sing the performance and work on it, I live through it now and see its relevance in the present moment. I do not have a premeditated idea that I want to convey. Everyone finds their own answers in Onegin. Or they do not. Or they find them, but not immediately, only after some time. Many creators of great works themselves could not always explain why they created them this way rather than another. Why does a flower bloom? One can think about that for a lifetime. Art asks questions more often than it gives answers.

A wonderful answer. Two pauses surprised me a little, pauses I do not remember from productions of Eugene Onegin I had seen before. During the first one Tatyana is alone downstage, and during the second it is you, Lensky. The pauses are quite long; the set is changed during them, but I do not think that is the only reason.

In my case, after the ball at the Larins’, where there is such a storm of emotions, you need to shift gears. Both the director and the conductor told me: take a pause, do not rush, feel the transition of energy and focus into the next scene. At that moment I need to sense how ready the audience is to switch into a more intimate atmosphere, where Lensky speaks with himself and with everyone as if one to one. I need the audience’s concentration here, and I myself need time to enter the right state. In many productions there is an intermission at this point, but in our production the duel scene follows directly after the Larins’ ball. So the pause is deliberate; it was the decision of both director and conductor. In general, the maestro fills every phrase and every pause with meaning. There are also pauses before the arias “In your house” and “Where, oh where have you gone?”; they must be felt, lived through. Before “In your house”, the real me, like Lensky, needs time to grasp everything I have said before, how I challenged Onegin to a duel, and when Larina exclaimes, “My God, in our house, have mercy on us!” I need to understand what I can answer to that, so the feeling of being stunned and the pause are entirely justified. Perhaps from the auditorium the pause does not seem long, but it lasts exactly as long as necessary and is never measured in advance; it is born in real time.

With whom among your partners in this production had you already worked before?

With many of them. With Ruzan, with Boris, with Elena Zaremba we sang Eugene Onegin in Dmitri Tcherniakov’s production in Vienna. It is always wonderful when you work with someone you already know and are friends with. This time we worked for a very long period, almost seven weeks, and everything was done exactly as we wanted.

The audience received all the performers warmly, but you especially, and deservedly so, in my view. The last time I heard such an impeccable Lensky was more than thirty years ago, here in Paris, at the Théâtre du Châtelet. It was sung by Neil Shicoff, Onegin was Dmitri Hvorostovsky, and the conductor was Semyon Bychkov as well. So many years have passed, yet the impression remains incredibly strong.

I know that production. When I was still studying, I searched for different recordings, discovered various tenors and came across Neil Shicoff. I greatly admired his performances, both in the Italian repertoire and in the role of Lensky. Many years later I met him, took part in his master classes, and never stopped admiring him. Perhaps I sing in a slightly different tradition, but tenors such as Nicolai Gedda and Fritz Wunderlich remain models for me.

I know that this summer you will make your operatic debut in Switzerland, singing Ferrando in Così fan tutte: the Zurich Opera House is reviving the production staged by Kirill Serebrennikov in 2018. Have you seen that production?

If I am not mistaken, it was not filmed, so I have seen only a technical recording. It will indeed be my operatic debut in Switzerland; before that I sang there only in a couple of concerts while on tour. I know Ferrando’s role extremely well, I have sung it perhaps more than any other. I am also planning to come to Geneva in a few years with one of my favourite productions, but I cannot speak about it yet, as the theatre must make the announcement first.

You work a great deal. Is there anything you would still like to sing but have not yet had the chance to?

Everything I would like to sing, and everything I have agreed to, is already in my plans, I simply cannot disclose it yet. In general, I try not to rush, because I truly sing a great deal and am constantly learning something new. There are roles I would like to perform, but I feel it is still too early to think about them, since they may be either too heavy for my voice or technically too demanding.

I know that this summer you will make your operatic debut in Switzerland. You will sing Ferrando in Così fan tutte. Zurich Opera is reviving the production staged by Kirill Serebrennikov in 2018. Have you seen that production?

If I am not mistaken, it was not recorded, so I have only seen a technical recording. This really will be my operatic debut in Switzerland. Before that I sang there only in a couple of concerts on tour. Ferrando’s role, on the other hand, I know extremely well. I have sung it perhaps more than any other. I am also planning to come to Geneva in a few years with one of my favourite productions, but I cannot speak about it yet, the theatre has to announce it first.

You work a great deal. Is there anything else you would like to sing but have not yet had the chance to?

Everything I would like to sing, and everything I have agreed to, is already in the plans. I simply cannot disclose them yet. In general, I try not to rush, because I really do sing a great deal and am always learning something new. There are roles I would like to sing, but I feel it is still too early to think about them, because they may be either too demanding for my voice or technically too difficult.

When the time comes, and I feel that I have found a technical approach to a role, I begin discussing it either with directors, or with conductors, or with my manager, or with theatre directors. In each season I have some new roles, whether in opera, chamber music, or oratorio, so I am constantly on the move, and I cannot overload myself either. I am focused on what I can do now and I do not look too far ahead, even though my schedule is planned four or five years in advance, and there is room in it for variations.

My voice feels comfortable now, and I keep it in that state, with small experiments, trying something new, but little by little. I am happy that I have found my repertoire, but sometimes I am drawn to lyric French repertoire. I would like to sing Faust, then perhaps move toward Roméo, Manon. I also sing twentieth-century music: Stravinsky, Britten, Prokofiev. In short, my task is to do well what I have already set out to do, and to keep moving forward.

I wish you with all my heart that all your plans come true, and I look forward to seeing you in Switzerland!