Lucerne Impressions

A couple of weeks ago, I already wrote about the history of the “Symphonic Piano” festival, which is part of the Lucerne Symphony Orchestra’s season. Those who missed that post can find it here. As for me, I will now share my impressions, and I do so with great pleasure, as they are entirely positive.

First of all, many thanks to the festival organizers for arranging perfect weather conditions. Blue skies and bright sunshine gave this already beautiful city, set on the lake admired by Sergey Rachmaninov, an almost fairy-tale quality. I simply could not take my eyes off the scenery.

More seriously, thanks are also due for the impeccable organization and the excellent concert programs, which made it possible both to hear once again works long loved and to discover something new, while also realizing that sometimes the same music can be heard in a completely different way. This last observation concerns the concert by Alexandre Kantorow. Only recently, on January 7, I heard him perform the same Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto at Geneva’s Victoria Hall, and it was very good. But in Lucerne, it was even better. I cannot say whether the reason lay in the pianist’s mood or in the special acoustics of the KKL, but the concerto sounded different.

Switzerland is currently being hit by flu and other seasonal illnesses. Musicians are not spared either, so the festival team had to make last-minute replacements. Thus, instead of the expected Christoph Eschenbach, Robin Ticciati appeared on stage alongside Alexandre Kantorow. The British conductor is no stranger to such substitutions. In 2005, for example, he replaced Riccardo Muti in a concert program at La Scala and thus became the youngest conductor ever to lead the orchestra of the Milan theater.

Instead of Brahms’s Piano Quartet No. 1 in Arnold Schoenberg’s orchestration, which had been announced in the program, the maestro “brought with him” to Lucerne Dvořák’s Eighth Symphony. This symphony is magnificent, and listening to it is a real pleasure, but in this particular context it felt a little too much to me. The concert, already consisting of three parts instead of the usual two, stretched to nearly three and a half hours. You know what the average age of classical concert audiences is like, so many people did not wait for the third part. That is a real pity, because it was then that Alexandre Kantorow, in addition to Nikolai Medtner’s Piano Sonata No. 5, superbly performed works by two composers I confess I had never even heard of. Here is what I found out about them.

The first is Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813–1888), whose real surname was Morhange. He was born into a Jewish family in the Marais district of Paris, an area historically marked by the presence of Jewish communities since the thirteenth century. His father, Alkan Morhange, was a private music teacher and gave his children their first lessons. Alkan later studied at the Paris Conservatoire, which he entered at the age of six, in the class of Joseph Zimmermann, himself a pupil of Cherubini. He pursued an active concert career until about the age of twenty-four, earning a reputation as one of the greatest piano virtuosos of his time, on a par with Liszt, whom, according to contemporaries, he even surpassed in technical skill in certain respects. Later, however, Alkan almost completely withdrew from public life, although in the final decade of his life he gave a series of semi-private chamber concerts in Paris, the so-called “petits concerts.”

At certain periods, Alkan taught privately and enjoyed a reputation as a first-rate pedagogue, as evidenced by the fact that after Frédéric Chopin’s death in 1849, his students turned to Alkan for instruction. Little is known about other aspects of Alkan’s life, except that he studied the Bible and the Talmud and translated into French the Old and New Testaments, the Talmud, the Torah, the Tanakh, the Psalms, as well as numerous works of ancient literature, including Greek myths, Horace’s Odes, Suetonius’s The Twelve Caesars, Aesop’s fables, the tragedies of Aeschylus and Euripides, Aristophanes’ comedy The Frogs, Ovid’s elegies, Dante’s Divine Comedy, and the philosophical teachings of Heraclitus of Ephesus and Democritus of Abdera. Sadly, these translations have not survived, nor have many of Alkan’s musical compositions. What has come down to us, however, is his cycle of 25 Preludes, written in 1844 and first published in 1847 as Opus 31. Alexandre Kantorow performed three of them, and they are simply magnificent.

The second composer is the Swedish contemporary composer and pedagogue Anders Hillborg. In Lucerne, the world premiere of his work The Kalamazoo Flow took place. The piece was commissioned by Alexandre Kantorow himself, with financial support from the Gilmore Foundation https://www.thegilmore.org/, whose headquarters are in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and of which Kantorow was named “Artist of the Year” in 2024. In May 2026, the work The Kalamazoo Flow will have its American premiere. Its title, like that of the city, comes from the local river. On that occasion, the project From Cliburn to Kantorow: A Celebration of Tchaikovsky will also be presented, bringing together the American and French winners of the Tchaikovsky International Competition in Moscow.

Roman Borisov fully lived up to all my expectations. In a demanding program, performed in one continuous flow, he demonstrated both his own artistic depth and intelligence and the excellent training he received from his Novosibirsk teacher, Mery Lebenzon. It is truly a pity that she did not live to see her student’s success. I hope that at one of the next editions of the Le Piano Symphonique festival, we will be able to hear Roman Borisov not at a daytime concert at the Schweizerhof Hotel, but in the main hall of the KKL.

The highlight of my two days in Lucerne was, as expected, the Friday evening concert entitled “Martha Argerich & Friends.” Such a format no longer surprises anyone, but in this case it was not about mere “friends” under whose name young performers sometimes try to advance their careers under the wing of established masters. This was a completely different story. A year ago, Martha Argerich, who will celebrate her eighty-fifth birthday this year, and Mischa Maisky, who turned seventy-eight on January 10, marked the fiftieth anniversary of their first joint performance in Verbier, long before the creation of the festival held at that alpine resort. That is the kind of friendship this is. Fifty years of artistic companionship could be heard in Beethoven’s Great Sonata No. 5, when piano and cello became one.

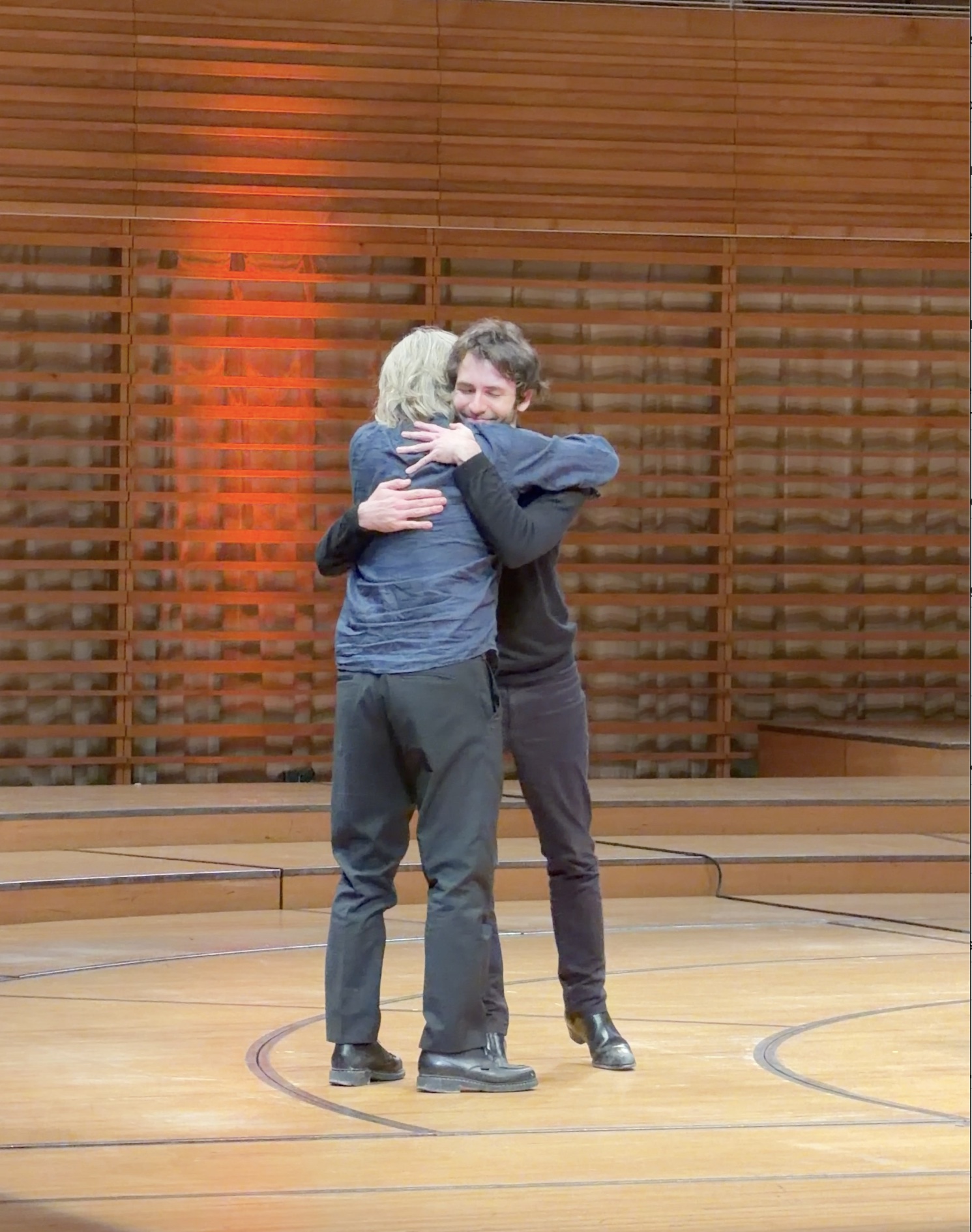

With the American pianist Stephen Kovacevich, born in 1940, Martha Argerich has a daughter, Stéphanie. There are no words to describe the emotions stirred not only by their music-making together, but also by their mere presence on stage. Stephen Kovacevich walks with difficulty. He approached the instrument in small, slow steps and took a long time to sit down, but what a sound they created together at two pianos in Debussy! And when, in the pause between En blanc et noir, written in 1915, at the height of the First World War, when Debussy had just been diagnosed with cancer, and the Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun in the composer’s own two-piano arrangement, they decided not to leave the stage in order not to waste time, the audience responded with warm, understanding applause.

The violinist Janine Jansen cannot boast such a long friendship with Martha Argerich simply because she was born much later. But the fact that she was welcomed into this groupe shows that the “senior colleagues” recognized her as one of their own, and they were, of course, not mistaken. To perform Beethoven’s “Kreutzer Sonata,” immortalized by Leo Tolstoy, who stayed in Lucerne in 1857 and wrote the short story of the same name, in such a way is only possible for true artistic kindred spirits.

When, at the end of the concert, the four musicians returned to the stage holding hands, the entire hall rose to its feet. I did not time the ovation, but it was long. It is for such emotions, for such moments, that one comes to a festival. I intend to return next year. And you?