A Violin Obsession

For the past ten years, I have blocked off the first week of February in my calendar: this is when the Sommets Musicaux festival takes place in Gstaad, attracting music lovers from many countries, who lend a markedly different tone to the crowd of ski tourists. Tourism here dates back as far as 1577, when the first inn was built at an altitude of 1,050 meters above sea level. The largest hotel still in operation today opened its doors in 1913 — the Gstaad Palace. I can already imagine readers smiling at the mention of this name: indeed, Roman Polanski made this unique establishment famous worldwide. Yet not all of the many celebrities associated with Gstaad stay in hotels; some own private chalets here, where the price per square meter can reach 35,000 Swiss francs. Alas, Gstaad is not only a stage for comedies, but also for tragedies: on September 2, 1980, Nina Kandinsky, the second wife of the celebrated Russian painter, was found murdered in her chalet, “Esmeralda.” They had married in February 1917, when Nina was twenty-three and Wassily fifty. Even today, celebrities can be seen strolling freely both along the Gstaad Promenade — whose concentration of luxury boutiques rivals that of many world capitals — and at Sommets Musicaux concerts, as well as at the dinners that follow them, held… at the Gstaad Palace.

Yet the true radiance emanates from the stages of the festival’s three venues: the churches of Saanen and Rougemont, and the chapel in Gstaad. Each year, the festival team succeeds in bringing together established masters and emerging musicians, ensuring discoveries and surprises alike. This year’s edition will be no exception.

Last year, the festival celebrated its first quarter-century; this year marks the fiftieth birthday of its artistic director, the French violinist Renaud Capuçon. Festival guests will be among the first to acquire his new album, released by Deutsche Grammophon to coincide with his anniversary — which he celebrates on January 27 — and devoted entirely to Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas. The organizers emphasize that this recording, a major milestone in the artist’s career, is the culmination of many years of reflection and preparation. It was made on the legendary Vicomte de Panette violin, crafted in Cremona in 1737 by Bartolomeo Giuseppe Antonio Guarneri, known as del Gesù.

According to specialists, this violin is one of approximately sixty instruments by the great master that have survived to the present day. After long wanderings, it became, in 1947, the property of the renowned American violinist of Jewish origin Isaac Stern, born in 1920 in Krzemieniec, in the Volhynian Voivodeship (then Poland, today in Ukraine’s Ternopil region), and taken by his family to the United States at the age of one. (Stern is also well known for his role in saving Carnegie Hall, whose main auditorium has borne his name since 1997.) He remained inseparable from the Vicomte de Panette violin for nearly fifty years, before selling it in 1994 to the American collector David Fulton. Fulton later resold it, for ten million dollars, to the Banca della Svizzera Italiana. On Isaac Stern’s recommendation, the bank entrusted the instrument to one of his former students: Renaud Capuçon.

The bows Capuçon used to record Bach’s works are no less remarkable. There are two of them: one was made by the French master François Tourte, who between 1775 and 1780 developed the bow model still in use today; the other, a Baroque bow, was crafted by the contemporary Italian maker Walter Barbiero. Specialists note that Guarneri violins are close in timbre to the mezzo-soprano voice and, unlike Stradivari instruments, allow for a more powerful bow attack on the strings — the bow which, according to Walter Barbiero, constitutes for a musician “an indispensable means of expressing his entire being, his thoughts, his emotions, his deepest self… music.” Isaac Stern, for his part, said that the violin is the most intimate of all instruments: it touches the body and responds to the heart. We shall therefore see how Renaud Capuçon brings these two aphorisms to life: as artistic director, he will open the festival with works by Mozart, performed together with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe.

Seasoned music lovers among my readers know that each year a particular instrument is designated as the festival’s central protagonist. Whether this is simply the turn of the violin in that rotation, or a discreet nod to Renaud Capuçon’s anniversary, one thing is certain: this year, the violin will reign as queen of the Gstaad ball. As mentor to the young violinists — whose performances can be heard at the afternoon concerts in the Gstaad chapel — Capuçon has invited his colleague Vadim Repin, whom Swiss audiences have not heard for several years. However, not everyone in Switzerland welcomes the arrival of the Russian violinist: like any artist who has not formally left Russia, he provokes disagreement. The organizers’ position, however, is simple: they do not engage in politics and regard Repin as an outstanding musician.

And so alongside a younger generation of violinists — Iris Scialom and Thomas Briant (France), Margarita and Elisaveta Pochebut (Ukraine), Ruslan Talas (Kazakhstan), Hana Chang (United States), Hawijch Elders (Netherlands), and Kurt Mitterfellner (Germany) — the Russian maestro will not only work on their existing repertoire, but will also bring to perfection Blue on Blue, a work commissioned by the festival from the French composer Yves Chauris. I will be especially pleased to hear the Pochebut sisters again on February 2; they took part in two concerts I organized in support of young refugee musicians from Ukraine — the first in Geneva in the autumn of 2022, the second in Gstaad in the winter of 2023, alongside the Sommets Musicaux. I suspect it was precisely then that Renaud Capuçon first heard them. And took note.

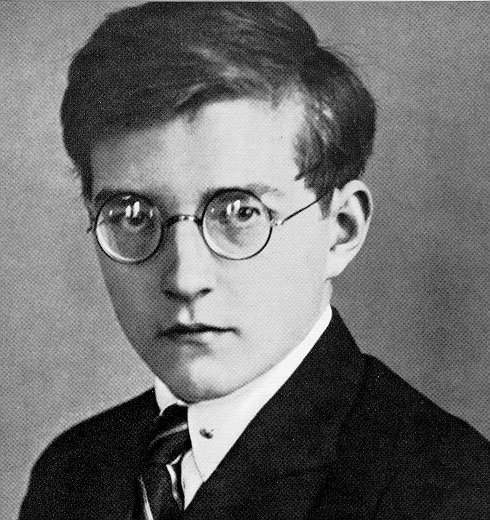

Vadim Repin himself will appear in Gstaad on Sunday, February 1. In ensemble with pianist Martina Filjak (Croatia) and cellist Julia Hagen (Austria), he will perform two landmark works of Russian music: Dmitri Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 1 in C minor, Op. 8, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Trio in A minor, Op. 50, In Memory of a Great Artist. Allow me to say a few words about them.

Shostakovich began work on his first piano trio at the age of sixteen, while still a conservatory student. The piece was inspired by youthful love: in the summer of 1923, while undergoing treatment in Crimea, the young composer met a Moscow girl named Tanya, to whom the work was later formally dedicated: Tatiana Ivanovna Glivenko. The premiere of the Trio, then titled Poem, took place on December 13, 1923, at a concert of student composers from the class of Maximilian Steinberg (son-in-law of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov) at the Leningrad Conservatory, performed by Veniamin Sher (violin), Grigory Pekker (cello), and the composer himself. After this early success, the work fell into obscurity for many years and was published only after the composer’s death, in the 1980s. It is worth noting that while the past musical year marked the fiftieth anniversary of Shostakovich’s death, the year ahead will celebrate the 120th anniversary of his birth.

Tchaikovsky’s Trio In Memory of a Great Artist, completed in January 1882, is dedicated to Nikolai Rubinstein, founder of the Moscow Conservatory, who died prematurely in 1881. Pyotr Ilyich felt deeply the loss of a man who had been dear to him as a friend, mentor, and outstanding interpreter of his music. Their relationship, however, had not always been smooth: Rubinstein initially rejected Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, deeming it unplayable — only later to perform it himself with brilliance. By deliberately entitling the work In Memory of a Great Artist, Tchaikovsky emphasized the universal scope of his conception, going beyond a purely personal dedication. An interesting fact: in November 1893, when Tchaikovsky himself passed away, it was precisely this trio that was performed at memorial evenings held in his honor.

The Sommets Musicaux program still holds many delights, including for young listeners: on the morning of February 3, in the church of Saanen, the French artist Grégoire Pont will create illustrations for Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, accompanied by Quatuor Fidelio.

For all further details, please consult the full program on the festival’s website — and do not delay: seating in the churches is limited, and demand is high.

See you in Gstaad!