World Literature Through the Faces of Its Authors

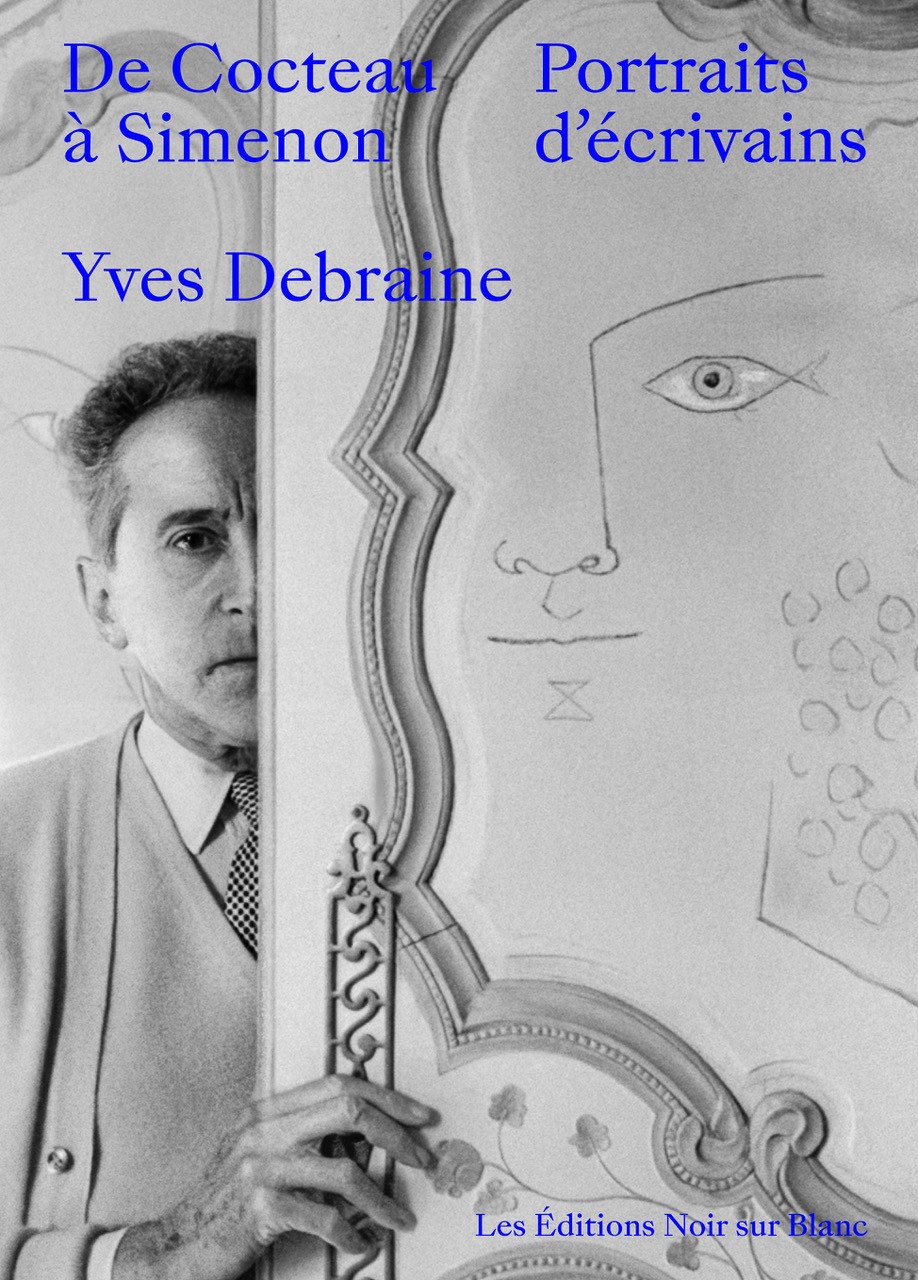

Two and a half years ago, I introduced my Russian-speaking readers to Luc Debraine – at the time the director of the Swiss Photo camera Museum in Vevey, as well as a journalist, photographer, exhibition curator, and lecturer at the University of Neuchâtel. I also wrote then that he devoted much of his free time to working on the archives of his father, Yves Debraine (1925–2011), a Swiss photographer of French origin who spent twenty years as Charlie Chaplin’s personal photographer and immortalized many remarkable figures of his time. Clearly, this archival work is progressing successfully: after a first album, Les Gardes-temps, a second has now appeared - De Cocteau à Simenon. Portraits d’écrivains.

The title says it all. These are indeed portraits of writers, from Cocteau to Simenon. Authors who wrote in different languages and sometimes held opposing views, yet remain united forever by Switzerland, by Yves Debraine’s lens, and now by this book – published on the centenary of the photographer’s birth.

No one could present this work better than Luc Debraine himself. In a six-page preface, he succeeds in evoking fascinating details about his father’s encounters with the writers he photographed, placing many of them in their essential historical context. At the same time, he conveys both his affection for his father and his admiration for a professional who, at the end of his life, kept Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations on his bedside table.

What a privilege it is to “participate,” suddenly, in a meeting between two great masters of detective fiction – Georges Simenon and Ian Fleming – which took place in the summer of 1963 in Échandens, in the canton of Vaud; or to discover how the young Yves Debraine came to possess Jean Cocteau’s duffle coat; or to learn of French filmmaker Marcel Pagnol’s abandoned project to adapt Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz’s Beauty on Earth; or, finally, to sense the impression made on Yves Debraine by Vladimir Nabokov’s gaze, “so steeped in intelligence.”

Luc Debraine deserves credit for his lucidity and humor. “Some of these great names of publishing world did not settle in Switzerland solely for the pure air, the tranquility, or the beauty of the landscapes. They also took good care of their savings,” he writes in the preface thus gently demystifying literary figures who, after all, were human like anyone else. His list is not exhaustive; these were not the only reasons that brought celebrities to Switzerland. Next to the photograph of the French writer Paul Morand – the grandson of the engraver Adolphe Petrovitch Morand, founder in 1849 of a bronze foundry in Saint Petersburg – one reads: “An anti-Semite and zealous collaborator of Vichy, he was forced after the war into exile in Vevey, where he remained for about ten years.” In 1934, Paul Morand published the anti-Soviet book Je brûle Moscou, in which the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky became one of the principal targets.

The photographs assembled in the book, accompanied by captions written by their author, are remarkable for everything they reveal about Debraine’s subjects – and for the way they invite us to search for a likeness between the writers and the characters they created, characters we all know so well. Some authors appear only once, others several times, but this should not be taken as any hierarchy.

Given the profile of my blog – the accent obliges! – among the forty-six writers featured in the book, I paid particular attention to three whose mother tongue was Russian, even though others – from Friedrich Dürrenmatt to John le Carré – also encountered Russia or made it a theme in their works. A curious coincidence: all three bear the name Vladimir. Yet how different they are!

“Russian, British, 1942–2019. A dissident and human rights defender, he spent twelve years as a prisoner of conscience in Soviet prisons and psychiatric hospitals. Vladimir Bukovsky was exchanged in December 1976 in Zurich for a Chilean Communist leader. Author of several works on totalitarianism and Soviet psychiatry.”

Let us add that the man exchanged for Bukovsky was none other than Luis Corvalán, and that among the three photographs of Bukovsky chosen for the book, the one in which he wears a chapka touched me particularly – one immediately senses where he had just arrived from.

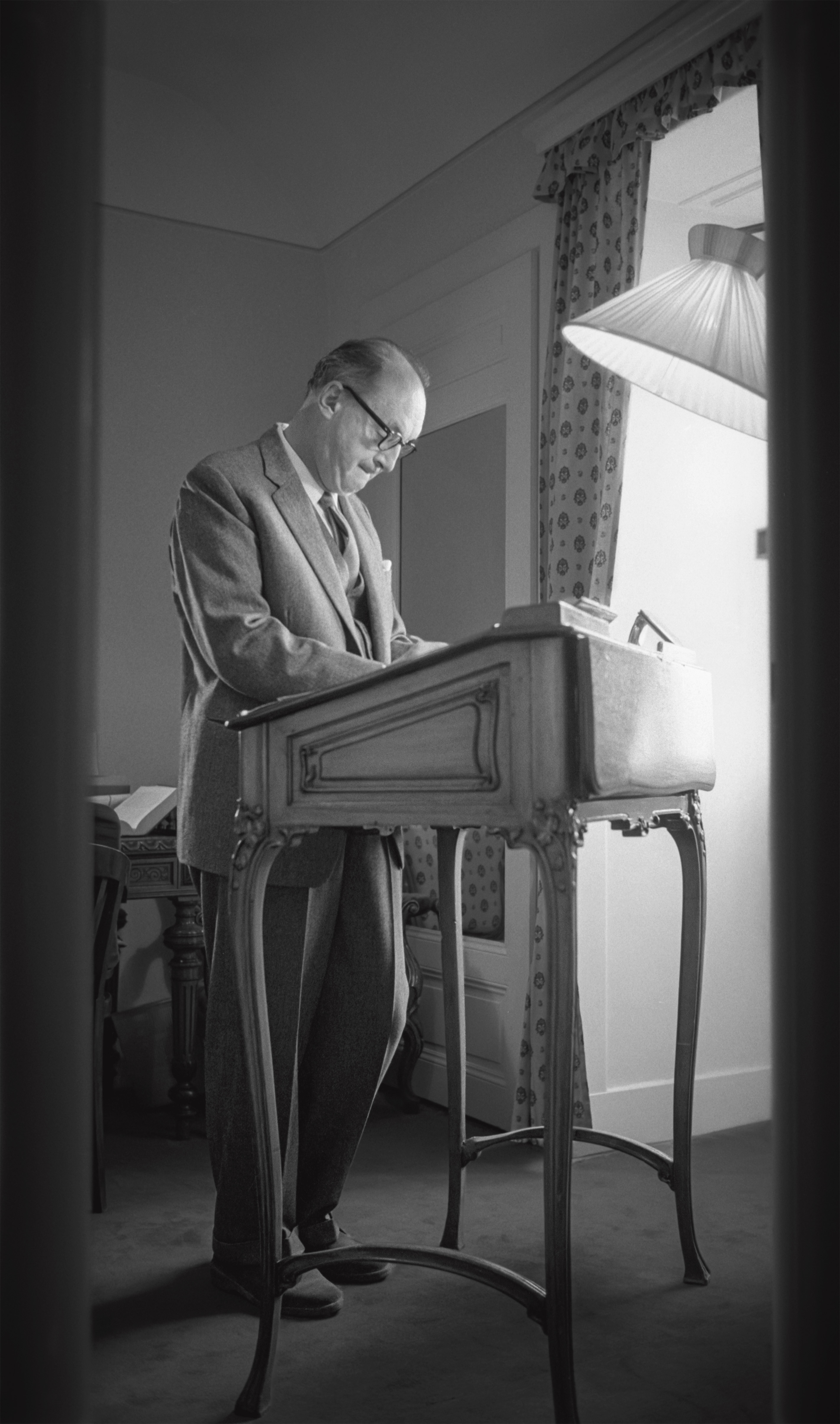

“Russian, American, 1899–1977. Vladimir Nabokov fled the Bolshevik Revolution for refuge in Britain, then Germany and the United States. He wrote his short stories and novels first in Russian, then in English. The French publication of his now-celebrated Lolita (Olympia Press, 1955) caused countless scandals. The book later achieved worldwide success. Vladimir Nabokov lived from 1961 until his death in 1977 in a luxury hotel in Montreux.”

A whole novel-like life, claimed by Russians, Americans, and Swiss alike, contained in a single paragraph. In the six photographs devoted to him, Nabokov appears at times completely absorbed in writing (always standing!), at others smiling and at ease.

The third Vladimir is less well known. “French, 1932–2005. Of Russian origin, Volkoff served as an intelligence officer during the Algerian War. Espionage nourished his literary work, from his early books for young readers to novels such as Le Retournement (Juillard/L’Âge d’Homme, 1979). He was also among the first French intellectuals to warn of the dangers of disinformation, dedicating six books to the subject.”

Yves Debraine photographed him in Lausanne in 1979. In his own words, Volkoff – known under the pseudonym “Lieutenant X” – preferred “to write in French, although I can write in Russian and English.” Only two of his works have been translated into Russian: Vladimir the Red Sun and Les Chroniques angéliques.

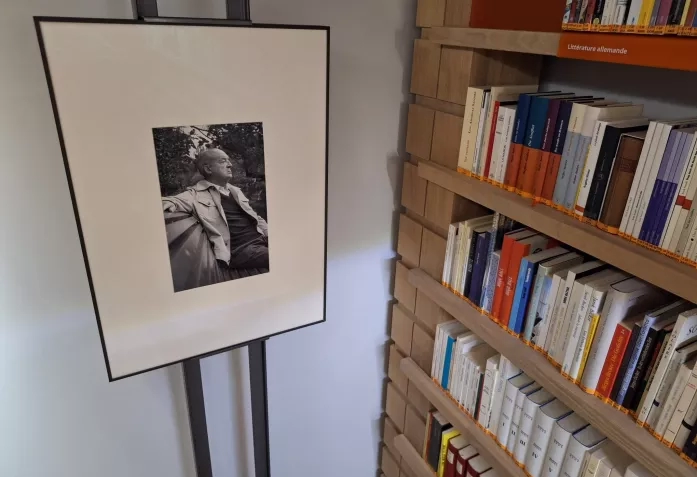

If you would like to admire the writers’ portraits up close, visit the Jan Michalski Foundation in Montricher (fondation-janmichalski.com): they are on display there until 18 January 2026. And while you are there, treat yourself to the book! A book always makes the best gift – and a book about writers even more so.

In the meantime, I wish you all, my dear readers, a Happy and Peaceful Year 2026!