«Deconstructing Félix»

In the beginning was... a buttock.

In all the years of my journalistic existence, I had never yet begun the story of an art exhibition with such words. But facts are stubborn things, and what can be done if it is precisely the "Study of a Buttock," painted in 1884 by the then 19-year-old Félix Vallotton (1865-1925) and now adorning someone's private collection, that catches the astonished gaze of visitors to “the” exhibition of the anniversary year of this Lausanne-born artist. A rather nice little buttock, which upon closer examination was not so "new" after all – it clearly belonged not to a young girl but rather to a lady of Balzacian age, which not only does not deprive it of charm but, on the contrary, lends it a particular mature beauty.

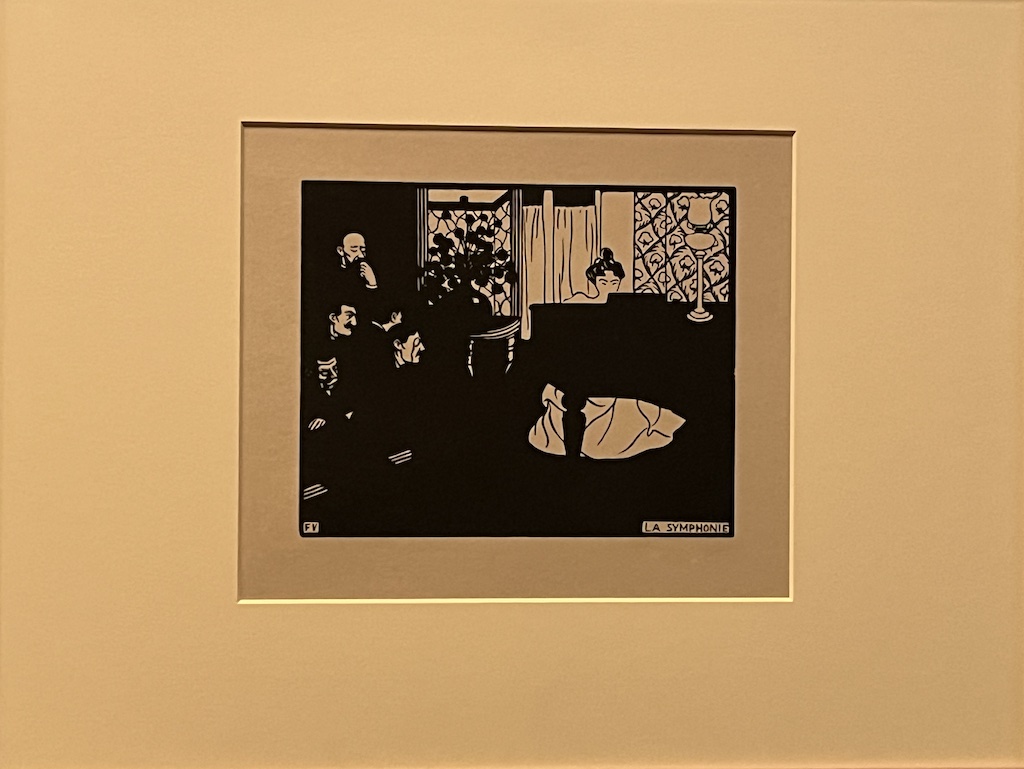

I don't know why the curators decided to open the exhibition with precisely this work, but it certainly sets a mood. The mismatch between this mood and that of the nearby portrait of the artist's parents, respectable Lausanne Protestants, makes clear why at the age of sixteen Félix Vallotton left his parental home once and for all and moved to Paris. His not unconfident determination is evidenced not only by this decisive step but also by the fact that, having studied at the Académie Julian, in the early 1890s he joined not just any art group but those who called themselves the "Nabis," which in biblical Hebrew means "prophet" or "chosen one". At that time, the group included Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, and Jean-Édouard Vuillard, who became Vallotton’s friends. (Incidentally, in the famous engraving titled "The Symphony," made in 1897, we see Bonnard and Vuillard attentively listening to Misia Natanson, wife of the publisher of La Revue blanche Alexandre Natanson and muse to this entire group, playing the piano.) Success came to Vallotton quite quickly: in the 1900s, his exhibitions were held triumphantly in Vienna, Munich, Zurich, Prague, London, Stockholm; his works were also exhibited in the Russian Empire – in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kiev, Odessa... And the first reproductions of his engravings were published in the magazine “World of Art” back in 1899.

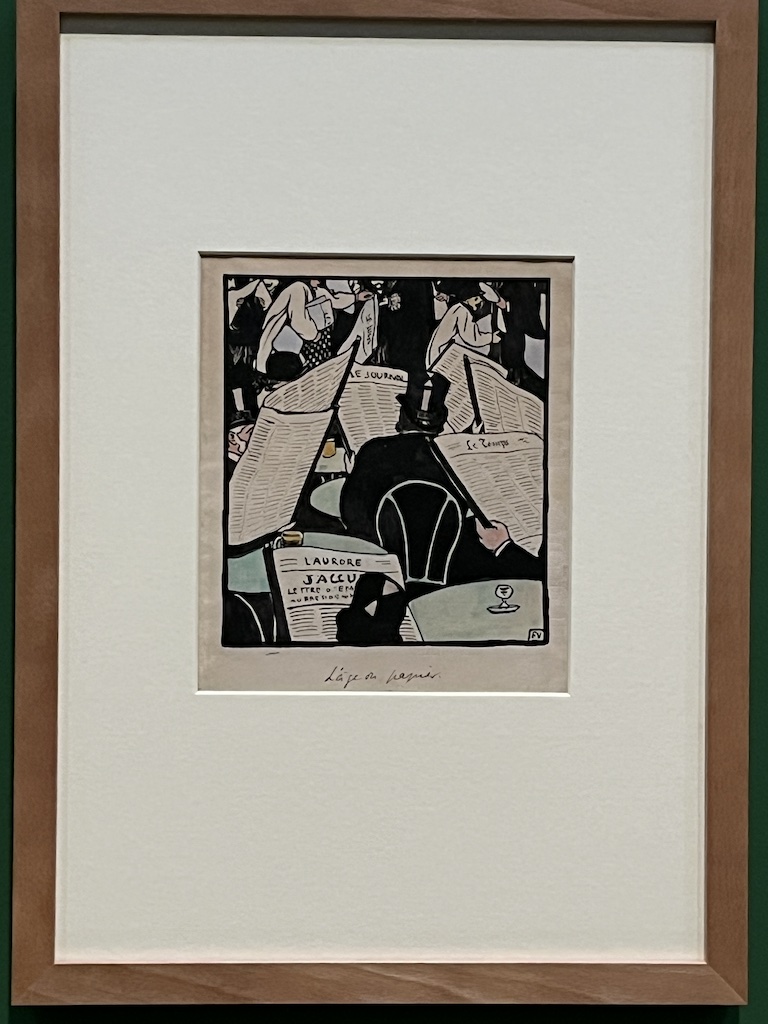

The Lausanne exhibition, organized by the cantonal museum together with the Lausanne Félix Vallotton Foundation, occupies two floors of the "Platform 10" space dedicated to temporary shows. It is both large-scale and dense – visitors can truly get an almost complete picture of the artist's work, which was distinguished by enviable productivity. Thematically, the exhibition is divided into twelve sections: Beginning, Crowd, Humor, Spectacle, La Revue blanche, Fashion, Repression, Interiors, Nudes, Landscapes, War, Final Years. These titles alone allow one to judge the diversity of the artist's narrative interests and his active civic position: ideologically close to the anarchists – in 1895 he created a portrait of Mikhail Bakunin – he collaborated closely with the journal "Le Cri de Paris" (The Paris Protest), one of the few publications that demanded a review of the Dreyfus Affair, and immortalized Émile Zola's famous open letter "J'accuse…" for this journal in 1898.

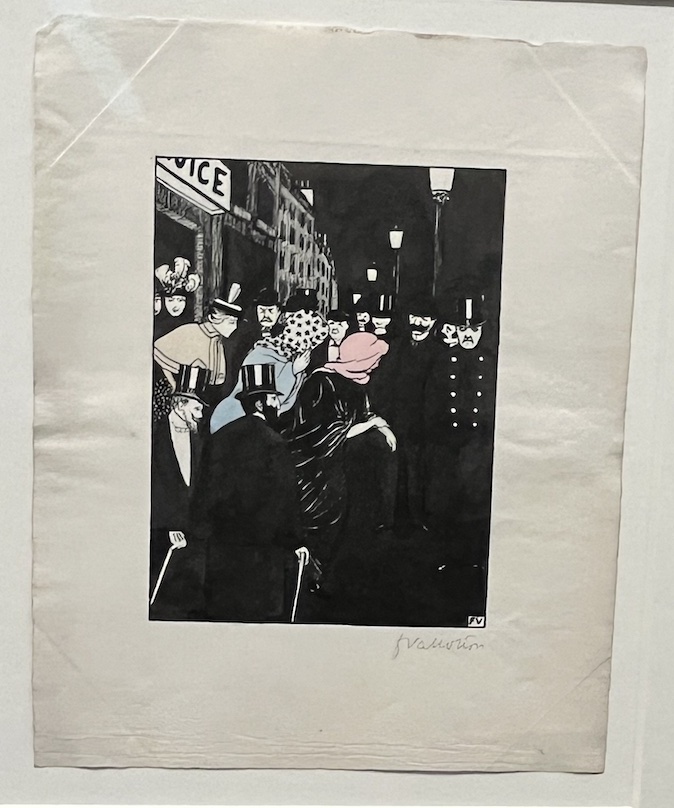

Three years earlier, Octave Uzanne, an outstanding French bibliophile and publisher, despite the anti-Semitic views attributed to him, commissioned Vallotton to create a series of drawings for a book titled "Badauderies parisiennes. Les rassemblements. Physiologies de la rue," which can be translated as "Parisian Gawkers. Gatherings. Street Philosophy." The theme was close to the artist's heart – by that time he had already been carefully observing crowds for several years, his sharp eye noticing interesting details on the streets, in parks, in shops, paying attention to how differently people behave in various situations – from ordinary rain to fire; when they think they are being watched or, conversely, that no one sees them. All these "notes" resulted in a series of amazing drawings, at once lyrical and ironic, reflecting the artist's sensitive soul and his sparkling humor. Initially, the drawings were done in black ink. But over time, deciding to sell them, Félix Vallotton added a bit of watercolor – touches of predominant soft pink and blue wonderfully enliven the black-and-white pictures.

A visitor interested in art who frequently attends exhibitions will easily notice that throughout his creative path, Félix Vallotton did not so much succumb to the influences of other artists or, even less, imitate them, but involuntarily absorbed what his colleagues were living through, simultaneously expanding both his own technical means and his color palette. Moving from room to room, one notes to varying degrees the traces of Bonnard, de Chirico, Magritte; one recognizes Modigliani's characteristic tilted head in "The Pink Bather" (1893), a reflection of Hodler in "Bathing on a Summer Evening" (1892-1893), an unexpected “hello” from Klimt in "The Waltz" (1893), and Chagall's flying Bella in "Crime Punished" (1915). And it would be very interesting to know how Roy Lichtenstein felt about Vallotton: his much later blondes come to mind when one pauses before the unexpected "Andromeda" born in 1918 – stylish, with a professional coiffure and lips painted with bright red lipstick.

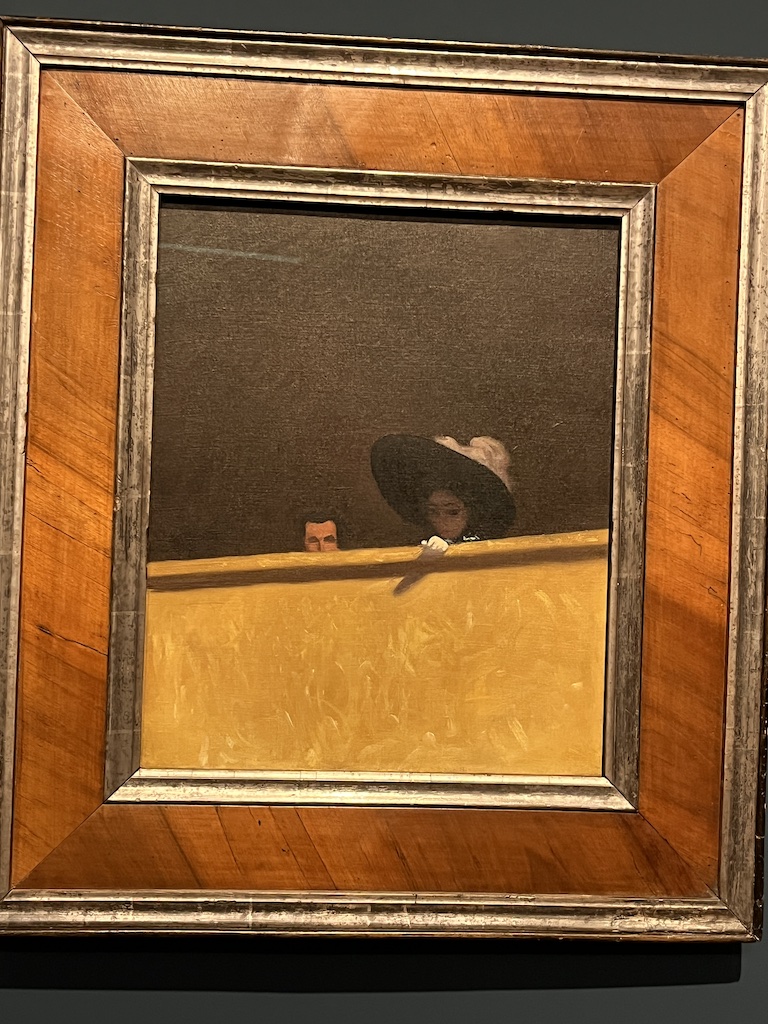

The exhibition curators did not skimp on various texts containing both biographical data about Félix Vallotton and explanations of specific paintings. However, the perception of the authors of these texts does not always coincide with that of “ordinary viewers”. For example, I very much liked the painting "Theater Box, Gentleman and Lady," created in 1909 and kept in the collection of an unknown Swiss collector – what a lucky person! According to the accompanying text, "between the man and woman a drama seems to be unfolding, indicated only by the white-gloved hand emerging from the shadow." Indeed, this gloved hand in the foreground immediately draws attention, only for me it did not indicate a drama but reminded of the image of Audrey Hepburn, this epitome of elegance, in "My Fair Lady."

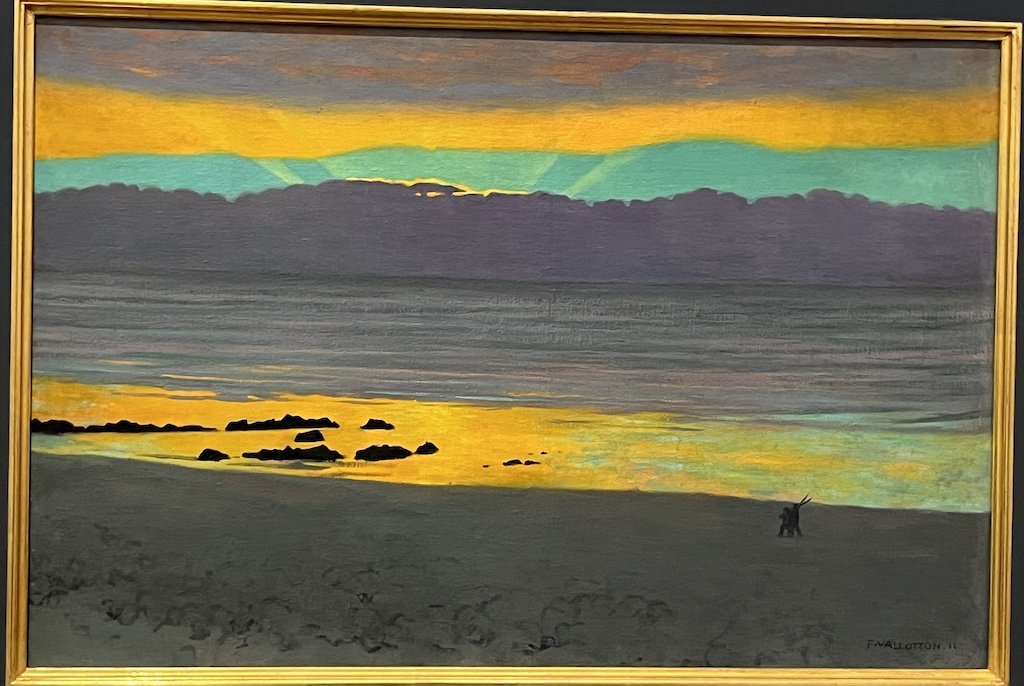

Vallotton's landscapes are very, very good, firmly established in his work from 1909 and over time transformed from purely realistic to slightly synthetic: one wants to plunge into these waves, stroll along these beaches, admire these sunsets, touch (and taste!) the luxurious peppers reflecting in the kitchen knife so that it seems to be covered in blood.

Throughout his life, Félix Vallotton painted not only sunsets and nudes. The exhibition allows one to judge how he himself changed, remaining, judging by the number of self-portraits, one of his own favorite models. If at the entrance to the exhibition we are greeted by a photograph taken in 1897 by Alfred Atys, in which Vallotton simultaneously resembles Lenin in a cap, his namesake Félix Dzerzhinsky, founder of Soviet secret service, and Russian actor Mikhail Kozakov, then we are, so to speak, seen off by a completely different Vallotton – gray-haired, rounded, carefully dressed, with an elegant pin in his neck scarf substituting a tie. And between these photographs – four self-portraits in which the artist captured himself at twenty (1885), having reached the age of Christ (1897), approaching fifty (1914), and shortly before his death, which occurred in 1925: Félix Vallotton died of cancer the day after his sixtieth birthday.

The exhibition will run until February 15, 2026; all practical information about it can be found on the museum's website www.mcba.ch. Highly recommended!

Выставка будет работать до 15 февраля 2026 года, всю практическую информацию о ней вы найдете на сайте музея. Очень рекомендуем!